10. The Brahmavihāra of Compassion

The meditative path to the All-Accomplishing Wisdom is via the Other Power practice of Compassion.

In Buddhist thought, the volitional aspect of Positive Emotion is called karunā, or Compassion, but this word also translates into the important English word Empathy – that intuitive aspect of Positive Emotion, without which Compassion cannot be understood and cultivated. Given the absolute centrality of Compassion in Buddhist thought, there is sometimes a great deal of confusion in our understanding of it – perhaps because it involves this somewhat complex way in which the volitional dimension of Compassion springs from the intuitive sensitivity that we call Empathy.

I believe Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’ is a practice that can serve to cut through this confusion because it is a ‘self-empathy’ practice – a Mindfulness practice by which we can attend to those objective and universal volitional energies within the body-mind that give rise to what we call ‘needs’, and therefore can begin to make sense of the complex inner world of feeling. To understand Compassion we need to find ways to understand suffering. Suffering in turn requires us to understand what we mean by ‘unmet need’. While suffering is a key focus in the Buddha’s teachings, it is itself a complex and subjective phenomena and not easy to fully understand. I believe ‘Focusing’ offers a path by which we can open up this dimension of awareness, and ultimately can develop both a true self-empathetic Compassion, and a corresponding compassionate Empathy towards others.

In this article, I am once again exploring the common ground between Buddhism and ‘Focusing’ and using this intersection to highlight some important but often neglected Buddhist themes – especially the placement of the brahmavihāras within the mandala-form psychological framework of Vajrayāna Buddhism. In this series, I have endeavoured to present a comprehensive survey of this territory, so please consider reading from the first article – Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Clear Space’. While the idea that Compassion is the ‘volitional’ brahmavihāra is regarded as self-evident by many (who associate it with the volitional samskāras skandha and with the Buddha ‘couple’ of Green Tara and Amoghasiddhi), I have Buddhist friends who associate Compassion with the Buddha’s Amitabha and Pandaravarsini, and the evaluative samjñā skandha (though this is a ‘Buddha couple’ that I, and many others, associate with mettā/maitri). So I am writing with a keen awareness of these differences of opinion and hoping my detailed exploration of the rationales for each set of correspondences, will help others to engage in their own contemplative investigation and come to their own knowing. An article that may be helpful in this regard is the fifth in this series: The Six Realms as Archetypal Psychology; and the sixth one Padmasambhava’s Hermetic Psychology. A listing of the whole series of articles can be found here: Buddha Meets Gendlin.

The Samskāras Skandha – Intuition and Volition

Opposite the vedanā skandha in the yellow southern quadrant of the mandala, we have the samskāras skandha in the green northern quadrant, where it describes the intuitive function of mind by which we recognise volitional dynamics (motivations, needs, purposes and energetic principles and processes) while also perceiving the volitional energies themselves – the volitional energies that give the egoic mind its momentum. Within the frame of reference of the five skandha self-illusion, these life energies are identified with, and therefore experienced as a personal will.

Perhaps understandably, many Buddhists imagine that spiritual practice is about developing this personal will – regarding the cultivation of that personal will as providing us with our only means of moral agency. If we find ourselves thinking in these terms, we need to refine our conceptualisations however, because the Buddhist tradition tells us that identification with the samskāras skandha causes us to accumulate kleshas in a category that it calls irshya – envy. This category includes fear itself, and all of the various types of avaricious and envious desires that human beings are prone to – when they have lost their compassionate connection to the real human needs of self and other, and have lost their sense of deeper purpose, or true meaning in life.

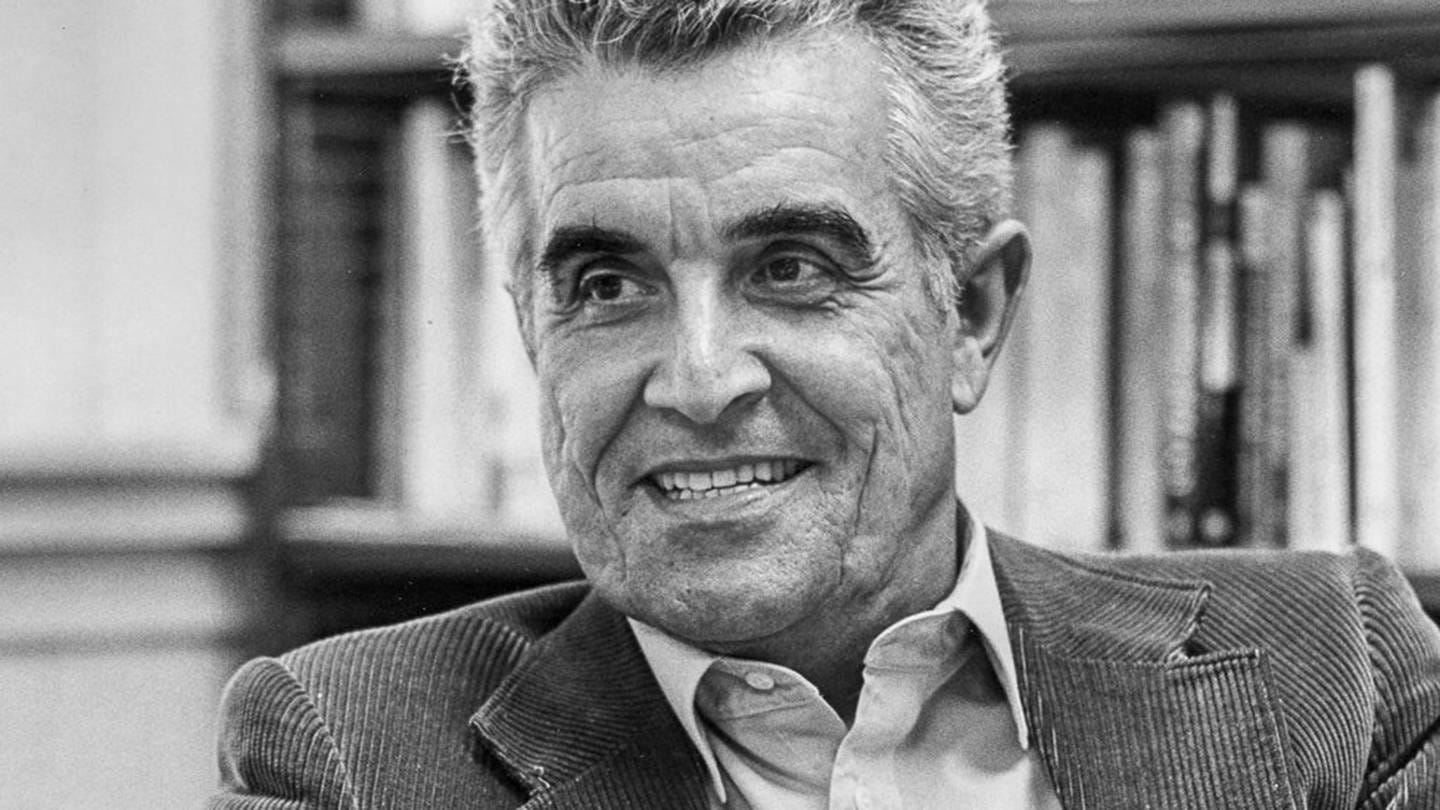

There is the potential, if we make this connection between the samskaras skandha and envy – if we see the extent to which egoic desire is almost always delusional – to see that it is not actually directed towards real needs and real satisfaction, but rather is the result of envious, or mimetic, social-psychological impulses, that are very primitive, unconscious and misdirected. Mimetic means imitative, and I am using the term here as it was used by the great French literary critic, anthropologist, psychologist and philosopher, René Girard (1923 – 2015), aspects of whose psychological, sociological and anthropological thought are profoundly helpful as amplifications of the archetypal psychology that is personified in the Asura Realm of Buddhism's 'Six Realms'. I find that Girard, originally a literary critic specialising in French literature, provides a powerful elaboration and explanation of the Buddhist understanding of the way desire leads to personal and collective dysfunction and suffering.

The word mimesis essentially means 'imitation', but René Girard uses the word mimesis to name a much bigger idea – a universal dimension of psychological reactivity that takes us to the heart of the human condition. For Girard, mimesis is the process by which envious, or mimetic desire leads to violence. He presents a view that is essentially identical to that of Buddhism. He proposes that human desire is fundamentally imitative and essentially envious – that we desire things not because of their inherent value, but because others also desire them. This false, or mimetic desire, is a sort of collective insanity that has always seized human societies. In the light of Girard's theory of mimesis, the only healing of this madness is through deep spiritual practice of the sort that we find in Buddhism and in Eugene Gendlin's Focusing. We need, in a sense, to reorient ourselves toward real desire, or real needs – and to an intuitive mode of perception that is guided by real Compassion (karunā).

The Asura Realm

So in the archetypal imagery of the Asura Realm, the Buddhist tradition is showing us that individual and social psychology cannot be separated – that our tendency to surrender, consciously or unconsciously to group processes driven by imitation, is profoundly undermining to our individuality, and cuts us off from more authentic and life-serving sources of motivation. Individuality requires us to surrender inwardly to the beneficial life energies of the universal human needs that are inherent in the dharmic reality. Surrendering 'outwardly', allowing our lives to be guided by the motivations (samskāras) of those in our social world, may appear to animate us – for a while. The samskaras are the component volitional energies that give us a sense of personal will, so allowing ourselves to be animated by the envious asura energies of the samskaras may even leave us feeling strongly motivated and dynamic. We may feel 'heroic' and competent, and we may tell ourselves that we are 'getting things done' even when we have profoundly lost our way, and lost our Compassion.

One of the disturbing features of human groups that have become unconsciously immersed in asura psychology, is the identification of scapegoats – suitable victims onto which the dark Shadow of the group can be projected, and towards whom the inherent violence of the group can be directed. This sort of social psychology was, of course, very visible in the rise of fascism in the 1930s, but it would be a mistake to imagine that this was a historical anomaly that modern liberal democracies have left behind. In reality, asura psychology has always been with us, and always will be – it is an inescapable part of the egoic mind. Religious communities, including Buddhist communities, are certainly not immune to the envious dynamics of the klesha category of irshya – indeed they can be remarkably prone to them. It is not uncommon, both in history and in the present day, to see churches and religious orders that have become ultra-hierarchical power structures where the Shadow is either projected down through the hierarchy, or onto the ‘out-group’ of non-believers.

The psychology of the samskāras skandha does not necessarily manifest in brutal interpersonal power games – the asura archetype may play out within us as internal conflict. There is conflict wherever there is fear – and there is fear everywhere, especially in those who claim not to be afraid, or are desperately trying not to be afraid. Where there is fear, there is a drive for control, and all manner of conscious and unconscious manipulations and conflicts will follow. Fear is an area where Gendlin's Focusing can be particularly helpful. As meditators, practicing alone or in a group, we can find it difficult to confront our fears and be with them and integrate them – we tend to disown them, unconsciously exiling them from awareness and developing compensatory strategies. The empathetic holding space provided by a Focusing 'Companion' may create just the conditions we need to address such stuck psychological processes. The Focusing model also has the great power of being able to support us to address two or more 'psychological parts' that are locked in unconscious conflict.

Religion and spirituality, in Girard's view, has always existed as a response to, or challenge to, the culture of mimesis – as an attempt to manage the violence that inevitably springs from the psychological dynamics of envious desire. It names the way we use intuition and empathy unconsciously in order to achieve the comfort of group membership – always instinctively protecting the solidarity of the in-group by polarising against external others, or the chosen 'scapegoat'. Girard unflinchingly addresses the way violence is pervasive but disowned, while also highlighting the way populations have always been manipulated by the 'enemy images' presented to them by their leaders. The propensity of even sophisticated, well-educated, liberal-democratic societies to fall into collective Shadow projections is insufficiently recognised. The scapegoating of other nations and groups, is evidence of the enormous psychosocial power of the dynamic that is outlined both in Buddhism and the Girardian view.

So, mimetic desire not only leads to conflict and rivalry, as individuals are seized by the impulse to compare and compete. Even more fundamentally, it drives conformity – and it profoundly undermines individuality. Girard warned us that the personal freedom that is held to be of such high value in the modern West, may paradoxically, be leading not to the real mental and emotional autonomy and rationality that we call individuality, and to an active, well-educated citizenry within a vibrant democracy, but to populations dulled by the obsessive accumulation process that we call consumerism, and who are in a state of ignorant and compulsive surrender of their individuality to group norms – and to the manipulations of the powerful. The fundamental dynamics remain those that the Buddha saw in ancient India. Like Girard, the Buddha's view was that only a depth of spiritual vision can save us from this malaise. He told us that only samādhi – a radical mental and emotional transformation through meditative alignment with the dharmic reality – can lift us out of this violent social and psychological dysfunction. Focusing, in my view, is one of those meditative disciplines that offers the promise of this sort of psychological rebirth and social renewal.

Modern liberalism, while it appears to represent an advance on the ethical sensibility of previous, more conservative and religious generations, is subject to the same memetic social processes. The liberal mindset of the European Enlightenment arose historically as a form of reaction against the terrible moral failure of the previous era, with its oppressive religious authorities; absolute monarchies; social inequality; and intellectual stagnation. Lacking a sense of how true ethics and true individuality are rooted in a beneficial transcendental reality however, liberalism can fall into the same patterns of Shadow projection, intolerance and violence, and can be seen to be showing a desperate lack of depth and wisdom. In the light of the asura psychology that we find in the Buddhist 'mandala wisdom', or in Rene Girard's analysis, we can see the same lack of psychological reflection on a societal level; the same willingness to engage in war; the same drive to find scapegoats and make them suffer. Clearly this is a challenging idea, and a dark one, but it describes the modern world very well, and it certainly fits very well with the social psychology that we find in Buddhism's archetypal cosmology of the 'Six Realms'.

It is easy to fall into the idea that a Sangha – a Buddhist spiritual community – is automatically immune from these egoic dynamics and from the corresponding dynamics of 'the group'. Some teachers will even say that competition between members of a spiritual community is good and should be encouraged. While deep practice of the brahmavihāras by a critical mass of the members of a particular Sangha will indeed change the culture so that it better reflects the Sangha ideal, the dysfunctional mimetic psychodynamics of 'the group' should be regarded as inherent – as an ever-present social reflection of the un-Enlightened mind. While the ideal of Sangha is a collaboration of true individuals in the service of the Enlightenment of all beings, it is important to acknowledge that, in reality, Buddhist communities of practice are always mimetic – that, perhaps necessarily, they are cultures characterised by imitation and mimetic rivalry, and by that same unconscious intuitive attention to what is motivating other Sangha members, that is characteristic of non-spiritual groups.

Clearly, we cannot condemn all mimetic behaviour within communities of practice. We just need to be giving an ever higher expression to that impulse. This is the purpose of the 'hermetic' psychology of the Vajrayāna – it shows us the brahmavihāras and Wisdoms that correspond to the egoic or group tendencies that we are caught up in. Because the power-dynamics of the samskāras skandha and irshya (envy) are so dark – and because the psychology of the Asura Realm is woven so deeply into our world – it is of great importance that we recognise the signs of this sort of Shadow behaviour, when they appear in our spiritual communities. The pressure to conform – or rather a culture of willing conformity – while it may appear as an aspiration towards communal solidarity and intellectual cohesion, is a clear danger sign. I cannot overemphasise the importance of our understanding of the spiritual meaning of asura archetype – since the asura archetype is the very opposite of Compassion, and represents a psycho-spiritual pattern without which Compassion cannot be understood and systemically cultivated.

An even clearer warning sign, is shadow-projection onto particular external groups. It is very easy for our Dharmic enthusiasm and drive for clarity to become framed as a sort of cultural battle – a cultural battle in which various groups are condemned in a belligerent style that is unbecoming for Buddhists, and remarkably lacking in Compassion. This is why the brahmavihāra of karunā (Compassion) is the healing principle for this dimension of mind. Compassion is the application of an intuitive style of psychological intelligence that empathises and recognises the real needs that are at play. It does not condemn, and it does not fight, and it does not turn people into scapegoats and adversaries. The dynamic compassionate intelligence of the Buddhist tradition empathetically recognises the psychology that is at play, and then responds with a non-adversarial intervention. This is the All-Accomplishing Wisdom.

The All-Accomplishing Wisdom

A non-adversarial intervention is one that avoids fighting with people, while also avoiding the tendency to invite people to engage in a fight with themselves. A Western Buddhism that is framed as a spiritual heroism (the 'self-development', or 'self-transcendence' perspective) so easily becomes an invitation to fight with ourselves. The dynamism and vitality of the Buddhist tradition is not an expression merely of the heroic however – rather, it is a compassionate responsiveness that arises from the deep, intuitive, psychological intelligence that we call Empathy. This is the All-Accomplishing Wisdom. When we enter into the three-fold 'self-discovery' perspective, we truly enter into the intuitive compassionate intelligence of the bodhisattva – and recognise the innumerable subtle ways in which the bodhicitta is at work in this world.

To recognise the bodhisattva archetype, is to learn what it is not – to learn to distinguish it from its various Shadow reflections in Western culture. We need to avoid regressing to the pagan level. We are not aspiring to become the merciless mythic heroes of the pagan world, the founders of the imperialistic, slave-owning states that were the origins of Western civilisation. We need also to avoid the belligerent posture of compassion that is the crusading spirit of Christianity – which slaughtered millions and destroyed civilisations under the banner of Jesus Christ. We need to avoid the Nietzschean spirit, that would live heroically in a world without a benevolent transcendental – an idea that the Nazis tested to destruction. We need to avoid the grand narratives of modernism and its delusional faith in 'science' and 'progress'. And we need to avoid the hubris and cultural imperialism of our post-modern Western liberalism, that loots the world and wreaks havoc in the name of free markets, while posturing about freedom and democracy.

The other skandhas and kleshas also play a part in the unconscious group dynamics of the provisional Sangha – especially the Hell Realm psychology of the narrative-creating rūpa skandha and its corresponding klesha category of dvesha (judgement, condemnation, hatred, etc.), that I have briefly outlined above – but the Asura Realm dynamics of the samskāras skandha and the klesha category of irshya (envy, jealousy, competition, fear and control) are just as important, and more easily overlooked. The egoic mind being what it is, we want what others want, and the personal will always functions within a social context. It is easy to imagine that we are finding our own motivation by attending intuitively to the motivations of others – whether those motivations be base or refined. In reality we are often merely copying the motivations of others – imitating those whose attributes we admire or envy. Buddhism challenges us to bring Mindfulness to these habits of mind – so that we are not just expressing a more spiritually refined form of irshya (envy), but finding authentic motivation and true individuality.

There is a view, held by many in leadership roles in Buddhist communities, that a Sangha primarily serves as a cultural venue in which we imitate and emulate those who are more spiritually developed. Paradoxically this perspective, which may be called a 'self-power', or 'self-development' perspective, advocates an approach in which we develop 'self-power' by harnessing this mimetic group-membership instinct and our impulse to intuitively attune to, and copy what is motivating others, so that we are animated, inspired, and motivated, by our energetic emersion in the Sangha group. This perspective, which may be called the 'self-development' approach, may serve us in the early stages of our engagement, but beyond a certain point in our process it can no longer serve us. Ultimately, the Buddhist path requires that we transcend the egoic mind's mimetic mode of functioning – by allowing non-egoic, or dharmic motivations to take over our lives.

What I am calling dharmic motivations here, turns out to be essentially identical to what I spoke of as 'real needs' above. Curiously, 'real needs' are ultimately not personal but universal – the samskāras are 'empty' of self-nature. The distinction that I am trying to make here is an extremely subtle one, but it takes us to the illusive and paradoxical heart of Buddhist wisdom. There are echoes of this wisdom everywhere. It was particularly evident and well-articulated in Neoplatonism. William Blake provides another important example. In his great poem The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, he wrestled with this idea that the true desire that leads to true satisfaction is not the problem. The problem is false desire – envious, or memetic, desire. Mimetic desire is that envious desire that does not express the deeper needs of our universal humanity. It is a group desire that undermines our individuality and innate ethical sensitivity.

This is a two part article. The themes I am exploring here are vast and hugely important. In my next article in this series [Self-Empathy Brings Integration], I shall continue to reflect on Compassion; the ‘empty’ nature of the will; and the question of how this ‘empty’ samskāras skandha is to be related to and transformed, or brought into alignment with the transcendental dharmic reality.

© William Roy Parker 2025

11. Self-Empathy Brings Integration

As part of my exploration of the common ground between Buddhism and Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’ dyad practice, I have been keen to present a brief survey of the inner and outer aspects of the brahmavihāras. The brahmavihāras are the attitudes of Consciousness that Gendlin directs us to – they are the attitudes of Mindful Presence, a…