12. Dimensions of the Buddhist Heart

Gendlin's Focusing as an experiential exploration of the territory that Western poetic tradition calls 'the Heart'.

The Buddha invited us to engage in a detailed experiential investigation of that inner domain of experience that Western poetic tradition often simply calls ‘the heart’. This is the domain of ethics and relationship; of meditation and devotion; and of mystical insight. When we are expressing our deepest existential longing, we may speak of ‘the heart’s desire’; and as spiritual aspirants (in Buddhist communities of practice or elsewhere) we may say we are learning to be guided by ‘the heart’s knowing’. ‘Heart’ is clearly a very important word in the English language, and both Buddhism and Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’ can be thought of as pursuing a deep engagement with it, so I would like to explore this word in this article – to understand it better and unfold its meaning.

Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’ teaches us to use words with precision – with a keen attention to what words actually ‘fit’ the phenomena of our experience. Buddhism teaches the same attention to the limitations of language – continuously warning us that we need to use language carefully, because words, while they are a path to wisdom, can only ‘point’ to reality, and can never completely capture it. We need to be aware that we can use a word like ‘heart’ in different ways – sometimes generally, metaphorically, poetically, idiomatically or rhetorically, and sometimes as a precise pointer to a somatic psychological reality. In my recent articles I have been engaged in an exploration of the skandhas – using my experience of the ‘Focusing’ approach to Mindfulness to take this enquiry to a more precise and experiential level. For various reasons, which I have tried to point out along the way, the skandhas are rarely approached with this sort of depth and precision – indeed rarely taken as the Buddha intended – as a guide to an experiential enquiry into the ‘empty’ nature of the body-mind.

In Vajrayāna tradition the notion of the heart is often quite a bit more specific and precise, frequently referring to that level of our ‘empty’ energetic being that is most keenly felt at the heart chakra. This location in the centre of the chest is regarded as both the somatic seat of the volitional and the organ of intuition – intuition being our capacity to perceive intangible archetypal patterns, meanings, processes, and motivations. Furthermore the heart is one of the places in the body where we most clearly feel our Other Power connection to the transcendental, or dharmic, reality – the source of our depth and authenticity. There is something of a tension between this specific reference to the somatic heart’s particular function in the body-mind, and the more general and imprecise notion of heart as a synonym for Positive Emotion and for inner life in general. I hope that this article will serve to shed some light on the distinction between these two meanings, and on the way they are connected.

This article is also intended to extend the line of enquiry of my previous two articles, which explored both the nature of volition as it is conceptualised in Buddhist tradition, and the experiential exploration of bodily-felt processes of volition that we find in Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’. I give time, in those articles, to an exploration of both the egoic and the dharmic expressions of this dimension of mind. On the egoic level we saw the manipulative, controlling, envious, and ultimately violent volitional impulses of the egoic will as they are personified by the Buddhist tradition in the imagery of the asura archetype. On the dharmic level of mind, the same volitional principle finds beatific and beneficent expression as Samaya Tara (Green Tara) and Amoghasiddhi – personifications of the brahmavihāra of Compassion and of the All-Accomplishing Wisdom.

This is the twelfth article in the Buddha Meets Gendlin series. It follows on directly from the eleventh article – Self-Empathy brings Integration. If you wish to read the whole sequence of articles, the first article is Eugene Gendlin’s Clear Space.

I cannot help feeling that the world is in a spiritual crisis, and needs us to collaborate to create a culture of spiritual renewal. The collective reality that we may call the human heart needs to be nourished by wisdom, by a wise kindliness, and by our bearing witness to the ever-present reality of a beneficent transcendental. For me the Buddhist tradition offers us the vision of a non-theistic transcendental dimension. This dharmic dimension, because it pervades mind and world, can, to the extent that we turn receptively towards it, support the unfoldment of our true compassionate humanity. For twenty-five centuries, Buddhism has been passionately engaged with this project, and while the tradition primarily evolved as a response to the spiritual needs of a pre-modern world that was very different from our own, it has much to say that can address our contemporary deprivation. As the great historian Arnold Toynbee (1889 –1975) said: “Religion is the serious business of civilisations”.

The collective change of heart that is needed needs us to better understand the human heart. The assumption that we already know everything about the human heart is part of the problem. The nature of the human heart is illusive – it has depths that are literally unknowable, and real understanding of its dynamics has remained illusive even in a world where the study of psychology is everywhere. The Buddha spoke of the un-knowability of the human heart in his teaching of the ‘emptiness’ of the five skandhas; and of its sublime and immeasurable depths in his teaching of the brahmavihāras. He often spoke of the heart’s healing and unfoldment as following a five-fold, or four-fold pattern, pre-figuring the ‘mandala wisdom’ psychology that we find in Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism. I would like in this series, to acknowledge some of these mandala-form frameworks in the historical Buddha’s teachings – the ‘Five Spiritual Faculties’ and the ‘Four Foundations of Mindfulness’ are especially important – but I find the skandhas (and their associated kleshas and Realms) and the brahmavihāras (and their associated Wisdoms) to be particularly profound.

Even though I set out to distinguish the two modes of usage of the word heart, I find myself talking of the heart both in a metaphorical, rhetorical, and poetic way, and also in reference to the heart as a specific location in our subtle anatomy – it is difficult to separate the two. There is a precision and specificity in the psychology of the brahmavihāras that can help us here. The ancient Indian brahmavihāras – Appreciative Joy, Equanimity, Loving Kindness, and Compassion – were recognised by the Buddha as universal and archetypal, and as the component elements of a comprehensive experience of Positive Emotion. The Tibetan Buddhist tradition brings further clarification to this model, appearing to view the brahmavihāras as occupying four superimposed energetic layers of Positive Emotion – the ‘surface’ bodies in the nested somatic anatomy of our subtle bodies. These layers are connected but distinct, so it is possible, for example, to develop mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness) to a limited degree, without developing Equanimity. This is an important consideration for meditation practitioners who want to cultivate the comprehensive and multidimensional emotional positivity that is implied by the term Positive Emotion. When we can practice Mettā Bhāvana in order to cultivate mettā/maitri, we are likely to also find ourselves cultivating muditā (Appreciative Joy) and karunā (Compassion), but we are unlikely to cultivate upekshā (Equanimity) unless we consciously set out to do this. Upekshā is an essential relational quality which is foundational and absolutely necessary for our development of Positive Emotion. It gives us our capacity to be with another – a quality that is essential to our practice of Focusing. If we are reactive, judgmental and punishing, there is no upekshā – and our cultivation of mettā/maitri will be fundamentally undermined.

I have spoken, in this series of articles, about how the healing of the heart and the cultivation of Positive Emotion, requires us to become deeply familiar with all eight dimensions of the brahmavihāras – and I have been advocating Gendlin’s Focusing as a Mindfulness practice that can support us to achieve this. To achieve this comprehensive state of Positive Emotion, in which all of the brahmavihāras are being established and in which all four nested layers of our energetic anatomy (that I mentioned above) are being healed of their accumulated kleshas, I find it helpful to draw on the Tibetan Buddhist experience. The Tibetan system that we find in Lama Anagarika Govinda’s Foundations of Tibetan Buddhism appears to imply that the brahmavihāras are located in the body as a nested hierarchy within the four ‘surface’ bodies.

The largest and most encompassing of these four nested energetic layers is the one associated with the heart. The Heart Body, or Volitional Body, is where we most keenly feel the volitional brahmavihāra of kurunā (Compassion), but this is also the location of the category of energetic residues that are accumulated by the volitional samskāras skandha, that we call the kleshas of irshya (envy). Both of these volitional currents, and the general state of this Volitional Body, are felt in the heart chakra (at the front and back of the body). This is the location of the anahata chakra of Indian tradition.

This somatic anatomy model identifies the brahmavihāra of mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness) as an energy that occupies the second body down. This somatic layer which we may call the Emotional Body, is also the location of the category of energetic residues accumulated by our evaluative samjñā skandha, and which we call the kleshas of māna (craving). This layer, the so-called Emotional Body is most keenly felt at the solar plexus chakra (at the front and back of the body). This is the location of the manipūra chakra of Indian tradition.

This Tibetan system identifies the brahmavihāra of upekshā (Equanimity) as an energy that occupies the second body down. This somatic layer which we may call the Mental Body, is also the location of that category of energetic residues that we call the kleshas of dvesha (hatred), which are accumulated by the activity our mentally divisive and concretising, or ‘form-creating’ rūpa skandha. This somatic reality that we are calling the Mental Body is most keenly felt at the hara chakra (just below the navel at the front of the body and at the base of the spine at the back of the body). This is the location of the svadhishthāna chakra of Indian tradition.

Of these four nested energetic layers, the one closest to the perceptual reality that we call ‘the physical body’ is paradoxically the most difficult to talk about and attempt to define. Provisionally we can call it the Psycho-physical Body, and it is where we most keenly feel the brahmavihāra of muditā (Appreciative Joy), which is the brahmavihāra that is most attuned to the sensory, the specific, and the concrete. This somatic layer that I am calling the Psycho-Physical Body, is also the location of the category of energetic residues that are accumulated by the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha, that we call the kleshas of māna (pride). Particular movements of energy associated with this category of kleshas, and with the sense of muditā, can be experienced in relation the base chakra. This chakra, which is located in the perineum, which is called the muladhara chakra of Indian tradition.

While this hierarchical arrangement which describes the way the brahmavihāras are embodied somatically is not well known, it finds frequent expression in the Buddhist tradition in the way the corresponding Elements are arranged in the five-fold structure of Buddhist stupa monuments. In the symbolism of the architectural structure of Buddhist stupas, the square base of the stupa corresponds to the yellow Earth Element, the sensory vedanā skandha, to the Equalising Wisdom, to the brahmavihāra of muditā (Appreciative Joy), and to the base chakra. The domed or spherical structure above the square base corresponds to the blue Water Element, to the mentally form-creating rūpa skandha, to the Mirror-Like Wisdom, to the brahmavihāra of upekshā (Equanimity), and to the hara chakra. The conical structure above that corresponds to the red Fire Element, to the emotional and evaluative samjñā skandha, to the Discriminating Wisdom, to the brahmavihāra of mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness), and to the solar plexus chakra. The up-turned crescent structure above the conical structure corresponds to the green Air Element, to the intuitive and volitional sanskāras skandha, to the All-Accomplishing Wisdom, to the brahmavihāra of karunā (Compassion), and to the heart chakra. While this knowledge is not necessary for practicing Focusing, it nevertheless resonates with Gendlin’s conviction that personality transformation is always reflected in bodily-felt experience.

So the human heart is complex and woven through with the energies of the transcendental dharmic reality, and what I am referring to as ‘the heart’ here, is not just the physical organ that pumps blood around our body, with such seeming tenacity and tireless devotion to its role throughout our lifetime. It is perhaps of the nature of the heart that we cannot help thinking about even the physical heart in a poetic way, and using it as a metaphor for the core of our being – and the location of our capacities for both self-determination and self-transcendence. It would seem that this recurring difficulty of separating out these two uses of the word heart, is related to the subtle somatic reality that I was endeavouring to unpack above. It is perhaps because the intuitive-volitional Heart Body completely contains and interpenetrates all the other layers of our cognitive-perceptual sensitivity, and is in some sense the location of our capacity for Empathy, that we think of ‘heart’ as the totality of our emotional responsiveness – even though the other three somatic layers, and the other three chakras, all play a significant part.

We usually tend to use the notion of ‘heart’ much more generally and non-literally however. In our most inclusive and idiomatic use of the notion of the ‘human heart’ we are simply talking about our inner life, and especially about the depth and subtlety of that inner life. So ‘the heart’ denotes the totality of the body-mind. Somatically, this includes bodily-felt sensing, bodily-felt emotion and evaluation, and bodily-felt volition and intuition; and psychically it includes the mind’s corresponding fantasies and visions, and flights of imagination.

We use the word ‘heart’ as a synonym for caring, kindness, compassion, and human sympathy in general. To ‘have a heart’ is to have empathy – to have a normal human feeling for our fellow man and woman. I have come across Buddhist practitioners who have a problem with empathy. It is one of the tragic paradoxes of Buddhist wisdom that it occasionally leads practitioners to prefer the sweeping but somewhat abstract Buddhist vision of Compassion over the personal specifics of empathy. They may even see empathy as an over-concern with the personal. While I also have a passion for understanding how the self-illusion might be transcended, my enthusiasm for Focusing as a Buddhist practice, is related to my conviction that Compassion must be rooted in the specific felt-experience of self-empathy and empathy. Engagement with Focusing practice, guarantees that Compassion is rooted in empathy – and, I would even say, in the All-Accomplishing Wisdom (which I spoke about in my last two articles).

We need to guard against speaking about the Bodhisattva Ideal in a way that makes Compassion abstract and impersonal, and overly muscular and heroic. Focusing teaches us that less is more, and that Compassion can be quiet and un-dramatic. While Buddhism’s great compassionate project of ‘saving all beings’ tends to look, to Westerners, like the activity of a heroic moral will, and seems to require a focus on development of external and behavioural capabilities, this is a reversal of the sustainable order of things. In practice, we need empathy, and an attention to the heart’s inner complexities – including those currents of motivation that are initially unconscious to the egoic mind – if we are to make the world a better place.

Thankfully, the sort of superficiality that I have been talking about is not characteristic of the Buddhist tradition as a whole. I would argue that the Buddha backed up his frequent assertions about the importance of kindness and friendship with approaches to Mindfulness that create a depth and breadth of real empathy. Mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness), we must remember, is a true valuing of all other human beings without exception, and a true valuing of their wellbeing. Indeed maitri (pronounced ‘my-tree’) is an attitude that aims to relate with maitri in such a way as to establish that same maitri in others. The Buddha’s attitude of maitri is one that fundamentally affirms that people have value independently of their practical usefulness and effectiveness; and that every tiny act of genuine empathy, integrity and open-heartedness is significant, even if it appears not to contribute significantly to Buddhism’s grand compassionate project of saving all beings from the suffering of samsara.

The Buddha advocated a commitment to a truly altruistic and emotionally positive attitude – urging his students to be psychologically intelligent and vigilant, and to guard against any falling away from the ideal of Loving Kindness into any sort of ‘ends justify the means’ mentality. Given the importance of the Buddha’s teaching it is understandable that such thinking might creep in. The last teaching of the Buddha is often quoted. We are told that his last words of guidance to his students were: “With Mindfulness strive on!”. This is a rendering into English by 19th Century translators, of the Pali words ‘appamādena sampādetha’. If we set aside the heroic prejudices of the Victorian translators, and translate that phrase with more care and nuance, we come to a very different rendering.

Indeed paradoxically, it is as if the Buddha was anticipating the fierce and perhaps zealous determination with which his students would want to preserve and spread his teachings, and was urging care and temperance in that important task. The word that gets translated as Mindfulness, in that instance, is not sāti (Skt: smrti) but apramāda, which means ‘vigilance’ – which in the context of Mindfulness practice means maintaining a particular quality of attention that looks within for what is incongruous in our actions of mind, speech and body. If Mindfulness is to lead to a developed ethical sensibility, it needs this quality of apramāda. The subtleties of Mindfulness are difficult to teach and difficult to learn, but Focusing provides a powerful framework for this subtle learning – it is especially useful for helping us to recognise and develop both smrti and apramāda.

I have seen practitioners who are passionately identified with Buddhism, and who see themselves as carrying the authority of the Buddhist tradition, and who nevertheless have, in effect, abandoned the subtle self-awareness that Mindfulness practice demands of us – instead placing their emphasis on extreme forms of egoic ‘striving’ that leave no room for the vigilance and humility of apramāda. The passionate advocacy of Focusing practice for Buddhists that I find myself repeatedly expressing in these articles, has in part come from having seen the tragedy of this sort of one-sidedness – and having seen the harm done as a result. It would seem that Buddhists can easily fall into a neglect of Mindfulness, and into confused and superficial understandings of what Mindfulness is – especially where there is this seemingly exclusive emphasis on the personal will, and on the assertion of a need for intense and sustained ‘striving’ as the basis for spiritual practice. I would like, in a later article in this series, to give time to a more detailed analysis of the three words – smṛti, apramāda, and samprajñāna – that get translated as Mindfulness, but I keep coming back to my conviction that true Mindfulness implicitly requires the sensitivity and discernment that comes from brahmavihāras practice – Loving Kindness, Compassion, Equanimity, and Appreciative Joy – and my conviction that Focusing practice is an extremely effective way for Western Buddhist practitioners to find this depth in their practice.

The story of the Buddha’s last discourse is often told with an emphasis on the ‘striving’ – implying intense effort of a personal will – and no attempt to unpack the word apramāda, which was at the heart of the Buddha’s message on that occasion. I cannot help feel that this teaching deserves the deeper interpretation that I am giving it here. It can certainly be argued that the discourse the Buddha delivered from his deathbed, was highlighting the need for the ethical vigilance of apramāda. Forms of spiritual aspiration that overemphasise ‘striving’, or give centrality to a crudely conceptualised personal will, are always in danger of losing sight of Mindfulness, and therefore also of the Compassion at the core of the Buddha’s Middle Way path. The word sampādetha that gets translated as ‘striving’ does not in fact mean ‘striving’ at all. The word pada means foot or step, and the emphatic prefix sam means together or completely. So the connotation of the sampādetha is more like accomplishment, or the final completion of a journey of many steps, and provides a poignant echo of the Buddha’s life-journey coming to an end. He is aware of his death approaching, while also acknowledging a sense of completion in of his own extraordinary accomplishment. Above all he is wishing to support has students with a final foundational teaching – appamādena sampādetha. Although he appears to speak with an impactful brevity, aware perhaps that is words will be memorised, what he is in fact saying is something more like: If you apply yourself with humility, and with a deep and true ethical vigilance, you too can accomplish nirvāna – you too will reach the final completion of the spiritual journey.

The rendering of sampādetha as ‘accomplish’ highlights of course, an association with the All-Accomplishing Wisdom – the Wisdom associated with the brahmavihāra of Compassion (karunā). The All-Accomplishing Wisdom is of course associated with volitional samskāras skandha. As I explained in my previous two articles, it is our personalising identification with the samskāras that leads to asura consciousness and to our delusional conviction that the egoic will must be cultivated until it can conquer all. The All-Accomplishing Wisdom is also the highest expression of virya (energy, determination, vigour) in the Five Spiritual Faculties. The All-Accomplishing Wisdom overturns our assumptions about the psychologically heroic attitude of the egoic will – it implicitly expresses the idea of integrating an Other Power (‘self-surrender’) view into our model of mind, and into our approach to practice. What the Vajrayāna calls the All-Accomplishing Wisdom is at the heart of Gautama Buddha’s Middle Way.

The Vajrayāna associates the All-Accomplishing Wisdom with the heart chakra – a location in the body that is associated with volition. The negative implication of this is that the heart’s deeper nature is obscured by our personalisation of volition and our drive for control – the drive towards domination of ourselves and others that we see personified in the imagery of the Asura Realm. The positive implication is that the heart chakra is like a portal into the universe of the volitional aspect of the transcendental – the dharmic motivational energy that the Buddhist tradition calls the bodhicitta. The approach of the Buddhist tradition is very like that of the tradition of Phenomenology in modern Philosophy (which was Eugene Gendlin’s area of expertise). Buddhism prefers to avoid metaphysics and talk about experience, but it acknowledges that the world of our experience includes, and is informed by, intangible metaphysical realities. The great Buddhist sages have always been happy to say that some things cannot be known. The accumulated experience of the Enlightened Buddhist teachers over many centuries has however given us the Dharma – a spiritual psychology and a system of Buddhist metaphysics by which the three trikāya levels (dharmakāya, sambhogakāya, and nirmānakāya) and an archetypal mandala structure of the human heart have been mapped out.

With this Dharmic map of the heart in our possession we can see the whole three-level hermetic structure of mind as a unity – we can see the Middle Way path of reconciliation that resolves the polarity of samsāra and nirvāna. When we undertake to open to the possibility that this mundane nirmānakāya reality is pervaded by an ‘eternal’ and un-knowable, but undoubtedly beneficent dharmakāya, the heart needs a map of the archetypal landscape of the dharmic territory, and for me this core knowledge is to be found in the ‘mandala wisdom’ of Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism. Indeed, for me, that mandala psychology of the Five Wisdoms and the four corresponding brahmavihāras contains an essential and inclusive summary of Gautama Buddha’s teachings – the Four Noble Truths expanded into a comprehensive vision.

The true way of the Buddha is a way of the heart, a way of balance, and a way of reconciliation and integration on successively higher levels – it is in the heart that we sense our conflicting currents of volitional energy and bring them into harmonious resolution. Mindfulness is explicitly inclusive and explicitly avoids conflict and extremes, and therefore also regards with suspicion, any call to go to extremes in our spiritual practice. So the Buddha’s call for apramāda – for patient attention, for staying deeply grounded in Positive Emotion and relational ethics, however ardent and determined is our approach to the spiritual life – is something for us all to reflect on and take on board. For me, Gendlin’s Focusing provides a beautiful expression of these Buddhist values and principles.

When we are first introduced to Buddhist practice, we can easily fall into the assumption that ‘will’ (or volition), and ‘feeling’ (our emotional and evaluative responses) are opposed in some way. Right Effort in the Buddha’s Noble Eightfold Path is often presented through a formulation called the Four Right Efforts – a formulation that often gets reduced to the idea that Buddhist practice involves the use of the will to control negative feelings and cultivate positive feelings by an effort of will. This line of thinking lacks the nuance and sophistication of the Buddha’s Middle Way in my view, and appears to completely fail to include the experience of Other Power – something that was a foundational cultural assumption for the Buddha’s disciples, and something that modern practitioners also eventually come to recognise. The ancient Indian word samādhi is often translated as ‘concentration’. It is a word that is probably best left untranslated however, because it has profound connotations of Other Power which are lost in translation. The human heart is an organ of meditative surrender – an organ of intuitive perception that naturally tends to evolve into a recognition or ‘knowing’ of the transcendental dharmic reality. To reduce the heart’s functioning to the action of a personal will is to deny the heart’s deeper sensitivity and its capacity to transform through spiritual receptivity.

I shall attempt a clarification of the Buddha’s Four Right Efforts in a future article in this series. Narrow and superficial psychological thinking can bring confusion and conflict to the heart, and can even do harm to the heart. Those who speak with the authority of the Buddhist tradition should take very great care to speak the truth – to refrain from re-framing the Dharma to make it accessible. The heart is indeed the seat of the fantasised personal will, but it is much more. It is the seat of volition in general – by which I mean it also serves as a channel for the motivational forces of the dharmic reality. Our access to these forces requires a devotional and meditative receptivity in our personal practice, but it also requires a cultural context which supports this sort of openness and ‘self-surrender’. It is important to understand that volition (samskāras), in fact arises from, and is ultimately inseparable from, processes of bodily-felt sensation (vedanā) and evaluative feeling (samjñā). The Buddha repeatedly drew his students attention to this three-fold sequence of conditions – sensing; evaluation; and volition – always urging them to distinguish these stages in the reactive mind’s cycle. Only by bringing deep introverted awareness to this cascade of body-mind factors, can we face reality and free the heart from its bondage to past conditioning.

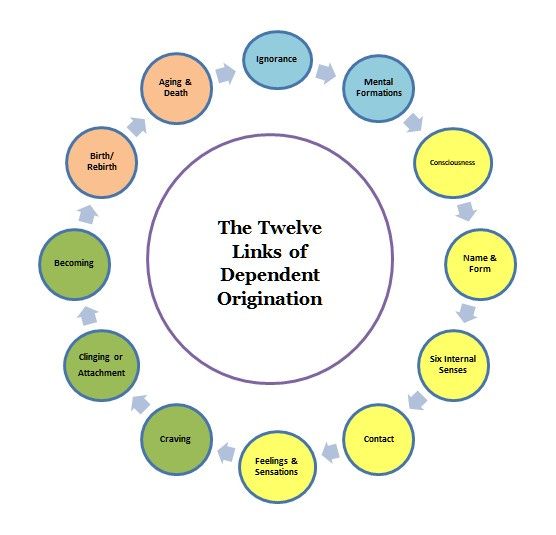

There is another well-known Buddhist formulation of this idea that presents the body-mind’s conditionality as a twelve-fold repeating cycle – the Twelve Links of Conditioned Co-production. It is an extremely complex model because it sets out to explain the law of karma by depicting the reactive mind’s process over three lifetimes – our previous life, our current life, and our future life. The very different mandala model of mind that we find in Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism, may be seen as a distilled version of the same idea of mind as a repeating cycle. At the core of both models is the heart’s three-fold sequence of conditions – sensing, evaluation and volition. In both models we find the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha leading to an evaluative response (samjñā skandha), and leading in turn to a volitional (samskāras skandha) response. In the Twelve-Links model however, the evaluative and volitional components are labeled differently. Indeed, in the Twelve Links model, the sensing (vedanā) process is expanded to explain the sub-stages by which our mentally constructed egoic identity (nāmarūpa), having a body and senses (saḍāyatana), comes into contact (sparśa) with our experience and generates our sensory perception (vedanā). In the Twelve Links, vedanā then leads the evaluative reaction of tṛṣṇā, or craving – which corresponds to the evaluative reaction of samjñā and the klesha of craving in the mandala/skandhas model. The resultant volitional process, that in the skandhas model is called samskāras, finds expression in the two links that follow tṛṣṇā. The first of these is upādāna, which is usually translated as ‘grasping’, or ‘clinging’; and the second is bhava (becoming), which refers to the volitional momentum of egoic existence – a volitional momentum of personalising self-identity that carries forward in this life and into the next.

The Twelve Links model begins the twelve-fold sequence with the same ‘spiritual ignorance’ (avidyā) that the mandala model places in the centre of the mandala – at the hub of the four-fold cycle. Indeed, in the Twelve Links, avidyā (ignorance) immediately follows conditions of bhāva (becoming), jāti (birth), and jarā-maraṇa (disease and death) in the previous life. So the Twelve Links model finds this almost universal ‘spiritual ignorance’ of avidyā, by which Consciousness (vijñāna) is always personalised, to be so karmically fundamental that it identifies avidyā as the conditioning factor that drives, and is present in, all volitional activities (samskāras) of mind, speech and body. These volitional energies (samskaras) are in turn the dominant conditioning factors that shape the personalised consciousness (vijñāna) that we carry forward (either in this life, or into the next). So, this personalisation of the experience of Consciousness through spiritual ignorance (avidyā) has an energetic momentum (samskāras), closing us off from the beneficial dharmic reality, and locking us into the dysfunctional twelve-fold cycle. Both Gendlin’s Focusing and Buddhism’s Mindfulness practices are practices for acknowledging the non-personal and dharmic nature of Consciousness – and for noticing the way the momentum of ignorance repeatedly pulls us back into egoic identification.

The mandala/skandhas model is somewhat simpler in several ways, but addresses the same key psycho-spiritual processes. Avidyā (‘spiritual ignorance’) and vijñāna (Consciousness), which are both located in the centre of the mandala, are intimately associated, since avidyā is the fundamental egoic klesha that gives our personalising identification with Consciousness (vijñāna) its energetic momentum. The ‘internal’ and ‘external’ functions that are our perception of the volitional energies of the samskāras skandha (green quadrant) are presented as conditions that arise from the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ aspects of the evaluative samjñā skandha (red quadrant), while also giving rise to the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ aspects of the describing, or ‘form-creating’, rūpa skandha (blue quadrant). The rūpa skandha in turn leads back to the ‘internal’ and ‘external’ aspects of the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha (yellow quadrant). So, in the mandala/skandhas model we have sensing (vedanā) leading to evaluation (samjñā); evaluation leading to volition (samskāras); volition leading to describing/form-creating (rūpa); and describing leading back to sensing (vedanā).

The Buddhas in the mandala below are personifications of the Wisdoms that arise as each of the skandhas is ‘seen through’. I wish I had an image of the five Buddha couples, since each Wisdom (and each brahmavihāra) has a ‘internal’ and an ‘external’ aspect. We each need reconcile the ‘internal’ and an ‘external’ aspect of the Wisdoms and brahmavihāras in ourselves, and this reconciliation is beautifully symbolised by the state of sexual union of each of Buddha couples.

All this is quite difficult to follow conceptually, and confusing because the same Pali or Sanskrit words appear to have evolved slightly different meanings in different contexts, and at different periods of Buddhist history. The mandala model of the skandhas that we find in the Tibetan Vajrayāna is a later synthesis, and is attributed to Padmasambhava (though it has its roots in the Buddha’s teaching), so I personally find that model more accessible and tend to give it more weight. Others prefer the Twelve Links model because it is earlier, and attributed to the Buddha. My overall position in regard to both models, is that they are meant to address our felt experience, and only serve us to the extent that we can relate all these Dharmic principles back to our felt experience. These ancient Indian words are little use to us if we cannot find what they are pointing to in our experience – and unfortunately, that resonance in our felt-experience is often difficult to find. The point that I find myself returning to, is that Focusing, because it is an experiential self-enquiry practice, and one in which we investigate our experience in an open-ended way, is ideal as a practice for exploring and finding the truth in these Buddhist models of the heart’s functioning. By giving us a practice framework for exploring our inner experience, Focusing gives us an extremely powerful tool for self-discovery – for discovering the nature of Consciousness and of the human heart.

In Focusing practice, we return again and again to these same sequences of conditions that the Buddhist tradition describes – the conditions that give the egoic mind its momentum. We start by adopting that phenomenological attitude in which we let everything be as it is – by refraining from any extraneous ‘internal’ or ‘external’ descriptions (rūpa skandha); by attending to the actuality of (‘external’) bodily experience and (‘internal’) felt-sense (vedanā skandha); by noticing the evaluative imagery (vedanā skandha) with which archetype and memory inform the felt-sense; by noticing the volitional component (the not-wanting and wanting), and having recognised the life-energy (samskāras skandha) and ‘life-forward’ direction in the process, we receive the insights and understandings (rūpa skandha) that something beyond the egoic mind wants to share with us. We may even come full circle, grounding these bodily-felt knowings by asking ourselves how this new life-energy wants to find concrete expression (‘external’ vedanā skandha) in our lives.

Within the ‘self-development’, or ‘self-power’ frame of reference, the Buddhist understanding of the psycho-spiritual cycle of conditions that sustain the egoic mind, appears to be focused on applying the egoic will to the task of breaking out of the karmic cycle of reactivity. When we fail to incorporate an Other Power perspective into our thinking however, this analysis is limited – because it is not clear how the egoic will can achieve its own undoing. Within the perspective of ‘self-power’, it may appear that the creative act – the acts of mind, speech and body by which we break out of the cyclical pattern of the egoic – is always, and must always be, an act of a heroic moral will. In fact however, creativity always involves the intervention of factors from beyond the egoic mind – indeed it would seem that ultimately the role of the moral will is to find humility, to let go of control, and to be receptive to these Other Power factors. Consciousness itself arises from beyond the egoic mind, and so also do all the brahmavihāra qualities that we are trying to integrate into our personality through meditation practice. All of these aspects of Other Power are found in Focusing practice, which, like meditation and Mindfulness practice, allows us to let go of the ‘self-power’ hubris of believing that the egoic will is the key – and of the delusional belief that volition (the samskāras skandha) is singular and personal.

So, if we step for a moment out of the specifics of the Heart chakra, we can say that ‘the heart’ refers to our deepest and most inclusive level of sensitivity and self-knowledge – to the whole realm of our inner life. When we become more deeply aware in that inner domain, whether through Buddhist meditation or Focusing practice, we find that all of the creative and evolutionary movements of mind involve not simply an act of the egoic will, but an opening to something beyond ourselves – they involve a surrender to some form of Other Power. The processes we call Integration and Positive Emotion are inherently a letting go into something beyond ourselves, a gathering of spiritual energies, and a radical opening of heart and mind.

© William Roy Parker 2025

13. The Four Right Efforts and Other Power

Continuing this series of reflections on the subtleties of how volition (the samskāras skandha) actually works in the context of meditation and radical spiritual transformation, I am feeling a need to explore the notion of Other Power more deeply. I would like to suggest that Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’ is a form of Other Power practice in several ways – the t…