6. Padmasambhava's Hermetic Psychology

From the Buddha's 'emptiness' of all five skandhas, to the mandala wisdom of Vajrayāna Buddhism.

These Buddha meets Gendlin articles are written with two purposes in mind. In part, they are chapters in a short book about the profound and comprehensive spiritual psychology that we find in the Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhist tradition. Integral to this purpose has been my wish to highlight the many areas of common ground with between Buddhism and Gendlin's Focusing model, and the ways in which my practice of Gendlin’s Focusing has led to a deepening of my Buddhist practice. I would like to especially welcome my non-Buddhist readers, and ask them to please bear with me – I really do hope that this series of articles is not too heavy on the Buddhism side, and that it is serves to educate Focusing practitioners about the value of the archetypal psychology of Vajrayāna Buddhism, as we engage with the inner world through Focusing practice.

While the spiritual realisation of Gautama Buddha and of the great Tibetan Masters like Padmasambhava was essentially the same, there is a clearly discernible process of ongoing conceptual refinement within the long history of the Buddhist tradition, and we need to acknowledge this. To this end, I shall be referring, once again to this evolution, within Buddhism's two inseparable domains of philosophy and practice, in terms of Dharmachari Subhuti's 'Three Myths' model – ‘self-development’ (self-power), ‘self-surrender’ (Other Power), and ‘self-discovery’ (Vajrayāna).

Clearly, the work of creating a comprehensive three-fold framing of Buddhism, that is fully adapted to the modern Western cultural situation is an ongoing challenge. I regard it as integral to our engagement as Buddhist practitioners that we participate in this work. This critical and creative engagement with the Buddhist tradition's translations and conceptualisations, follows naturally and inevitably from our deep contemplative engagement with the historical material. I regard this work as urgent and necessary, and integral to the goal of creating a Western Buddhism that can meet, and challenge, and engage creatively, with the modern version of samsarā that is the Western cultural and geopolitical situation.

This is the sixth article in this series. You may wish to read from the beginning of the series: Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Clear Space’. You may also wish to read the previous article: The Six Realms as Archetypal Psychology – as that would serve to frame the information in this and the next few articles.

I regard the Bardo Thodol texts that are attributed to Padmasambhava, as a profound source of spiritual knowledge. I am saddened to find that other Western Buddhists seem to find them either rather inaccessible, or simply not very useful. This is perhaps not surprising however. The central text of the Bardo Thodol does appear to be a strange Tibetan Buddhist funeral rite – a text to be read over the dead body during the days immediately after death, to provide reassurance and guidance to the spirit of the deceased.

I find that particular text to have an extremely profound general relevance in at least two ways. Firstly it provides answers to the perennial human question of how best to be with the presence of a loved one after their body has died. While the cultural and spiritual context of the text may be foreign to us, it expresses a beautiful response to the event of a death, and a very helpful general approach to prayer and meditation on that occasion – one that we can all learn from.

Secondly, and perhaps even more importantly, that same central Bardo Thodol text – the one that describes the visionary journey of the deceased person, and the spontaneous appearance of each of the figures of the 'Mandala of Peaceful Deities' (that came to be called the Dharmadhātu Mandala). By stating the skandhas, kleshas and Realms, and Wisdoms associated each of the 'Buddha couples' that are revealed in the intermediate state, or bardo, between lives, the text presents a powerful and sophisticated spiritual psychology, and is a treasury of Dharmic riches about the nature of mind.

Each 'day' within the first five 'days' (not days in our mundane time, of course) of the bardo process, the spirit of the deceased person encounters one of the Jinas, the five great archetypal Buddhas of the sambhogakāya – Vairocana (white), Vajrasattva-Akshobya (white/dark-blue), Ratnasambhava (yellow), Amitabha (red), and Amoghasiddhi (dark-green). So on each of the 'days' of the intermediate state process, we encounter different dimensions of the fundamental dichotomy – the polarity of the reality of Enlightenment, on one side (the five Wisdoms and Buddha couples that embody them); and the tendencies of the egoic mind, on the other (the skandhas, kleshas, and Realms).

So, the Tibetan tradition tells us that, in the intermediate state, we are shown the way karma works, and get an opportunity to experientially recognise the momentum of the egoic mind, and to sense the particular energetic characteristics of each of the Realms of rebirth that have been our destiny in previous lives. At each stage, we are also presented with an opportunity to see ourselves very clearly indeed – to see that, even though the karmic momentum of each aspect of the egoic mind may be very strong, we are also innately drawn to the corresponding Wisdoms and Buddhas. We therefore have an opportunity, in the intermediate state, to recognise the habitual choices that we have been making – perhaps over innumerable lifetimes. If, through our contemplation of these choices in our spiritual practice, we have sufficient clarity of intention and presence of mind, we may even gain liberation right there in the intermediate state – recognising the radiance of one of the archetypal Buddhas as the light of our own true nature.

For me, the question that some Western Buddhists often ask, as to whether the intermediate state process that is described in the Bardo Thodol is objectively true or not, is irrelevant and a distraction. The wisdom in these texts is abundant and obvious. They communicate profound and comprehensive information about the sambhogakāya level of mind and our relationship with it, and they do this powerfully through the symbolism of the archetypal Buddhas and archetypal Realms – while also setting out a comprehensive system of Dharmic psychology. I shall, in the five articles that follow in this series, be attempting to outline something of the meaning that is presented to us in the Bardo Thodol texts – something of the nature of these five dynamic relationships between the opposing reactive and creative potentials within the mind. These polarities play out in our minds every day throughout our lives. It is of great importance that we become deeply familiar with them.

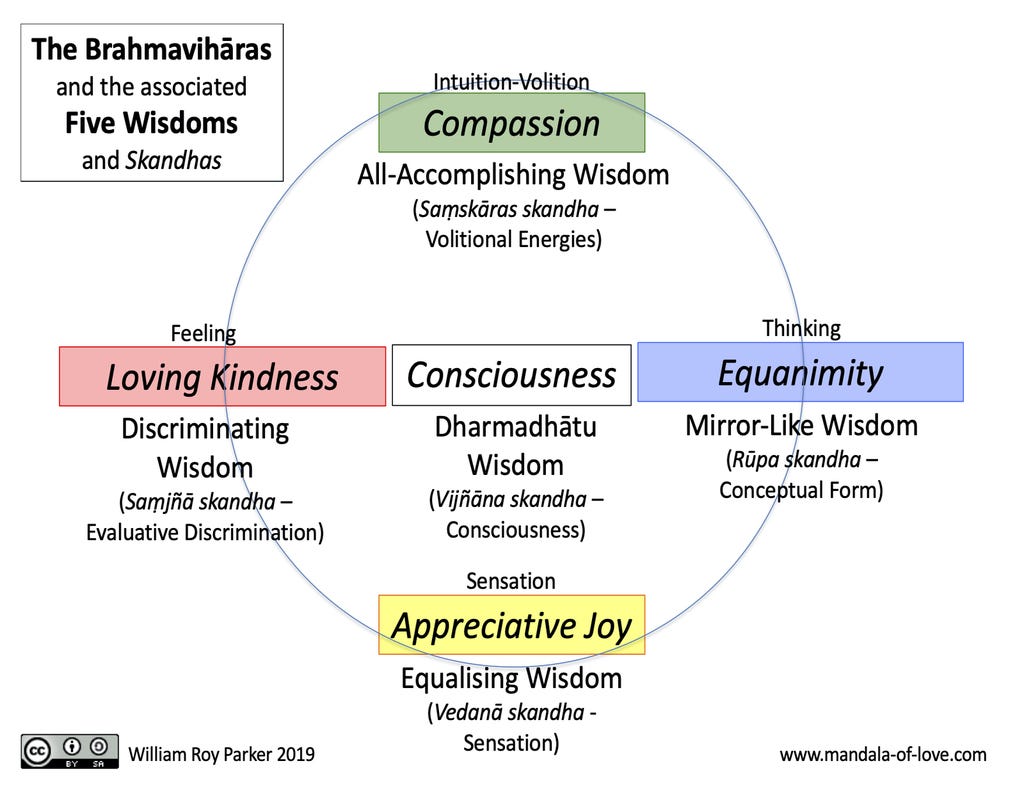

In order to highlight these five fundamental choices, these five dichotomies, I am especially keen to establish an understanding of the correct correspondences between the skandhas and the brahmavihāras. Because the brahmavihāras are not mentioned in the Bardo Thodol, I, like many practitioners, have had to work these out for myself. To do this 'working out' of the brahmavihāras that correspond to the Wisdoms, we need to unpack as much of the Bardo Thodol symbolism as we can, and we need to get very clear on the nature of each of the skandhas – something that requires very deep reflection in itself. If we approach this in a multidimensional way (addressing all of the elements of the model simultaneously if we can) we find that this working out is easier – or at least is very much easier than if we take only the skandhas, or only the kleshas, or only the Realms, as our starting point, as many often do.

In essence, our guiding question in regard to each quadrant of the mandala, is: Which brahmavihāra pair (i.e. 'self-regarding' and 'other-regarding' pair) best corresponds with the pair of qualities that a particular archetypal Buddha couple embodies – given their associated skandha-Wisdom? Each of the elements in this complex system of Dharmic psychology, serves to bring additional dimensions of clarity to our understanding of these apparent polarities. By understanding these polarities deeply, we can go beyond seeing them as opposites. We instead start to see them as hermetically related – as lower and higher expressions of the same archetypal principle.

While I believe this hermetic, or archetypal approach to the integration of the brahmavihāras into the Bardo Thodol's psychological system, is the traditional one – and certainly the most true to the Vajrayāna method and philosophy – it may not be familiar. Indeed, I have several dear friends, whose opinions differ. It has been quite unsettling for me to find that the contemplations of others have brought them to a different set of correspondences. I have been grateful for these discussions and differences of opinion however, because they have taken me back to the enquiry in a fresh way, and with a renewed commitment to objectivity. I have not however been able unlearn what I have found to be deeply and consistently true in my contemplative experience over the years. I need to emphasise once again however, that what I am offering, even if it is offered with conviction, is merely a point of view – and it is offered with an invitation to the reader to engage in their own enquiry, and their own contemplation of the traditional material.

The 'internal' and 'external' aspects of the brahmavihāras have been the foundation of my meditation practice for many years. I have found this deep engagement with the brahmavihāras to be powerfully transformative. Indeed, I attribute much of the depth of transformation that I have experienced in recent years, to brahmavihāras practice. When we practice the brahmavihāras in the spirit of Other Power, and of 'self-discovery', we come to recognise the 'always on' availability of these dimensions of Positive Emotion. They are direct bodily-experienced reflections of the skandhas and Wisdoms, and they are experienced as objectively and collectively existing archetypal, or sambhogakāya, realities.

Briefly, the skandha-brahmavihāra correspondences that work for me are the ones set out in the diagram above. If, when you read through the rationale for these associations that I have set out in the five articles that follow this one, you find that they really do not work for you, please just continue to utilise your own preferred set of correspondences. Please also contact me and share your alternative perspective and alternative rationale. I would very much appreciate your detailed feedback, even if it is critical. Please be sure to read the previous article however. In that article, which you can read here, I have discussed, in some detail, the various alternative sets of correspondences that I have come across – and have sought to distinguish the 'self-discovery' (Vajrayāna) approach to the correspondences, such as I have used in the following articles, from other approaches that are guided by other principles, or by the perspective of the 'self-development' ('self-power') approach.

© William Roy Parker

Consider reading the next article in the Buddha Meets Gendlin series:

7. The Brahmavihāra of Equanimity

This series of articles is a sharing of a contemplation that I have been engaged in for many years – a contemplation that I hope will be of interest to both Buddhist and Focusing practitioners, and especially those who are students of both. Buddhism and Focusing share a deep engagement with the inner world of visionary and bodily-felt experience. I have…