9. The Brahmavihāra of Appreciative Joy

The path to the Equalising Wisdom is via the Other Power practice of Appreciative Joy

This is a key article in this series. Gendlin’s ‘Focusing’, because it brings such intense Mindfulness to our internal bodily-felt experience, allows us to bring an important clarification process to the way we talk about the experience of ‘feeling’ within Buddhist communities of practice. I shall be talking in detail, in this article, about the extremely important ‘vedanā skandha’ – a perceptual function that most often gets translated by the word ‘feeling’, but which I much prefer to render as ‘sensing’. Because ‘feeling’ has multiple meanings in English usage, I am, like several others who write for a Buddhist audience, of the opinion that it is not precise enough, and therefore not the best translation – even though it was the translation used by my teacher, Sangharakshita, and many others in the Buddhist world.

Indeed, by far the majority of my Buddhist friends – people I have great love and respect for – translate vedanā as ‘feeling’. So I do not suggest this alternative translation lightly. My preference for translating vedanā as ‘sensing’, or ‘sensation’ however, is based on over four decades of deep reflection and contemplation. My love for all those of my Buddhist friends who use ‘feeling’ as their translation of vedanā, has not able to bring me to ‘unlearning’ what I know to be true. Indeed it is the love and care that I feel for my Buddhist spiritual friends, and for all the Buddhist Sanghas around the world, that obliges me to offer this suggested clarification. As always, this suggestion is offered in the spirit of that attitude that the Buddha himself frequently expressed – take what I am suggesting as a tentative proposal and see if it fits your experience. If the word does not fit your experience, find a better word – this was a foundational principle for both the Buddha and Gendlin.

To begin at the beginning of the Buddha Meets Gendlin series, read Eugene Gendlin’s Clear Space. The previous article to this one is The Brahmavihāra of Loving Kindness.

The Sensing and Sensory Vedanā Skandha

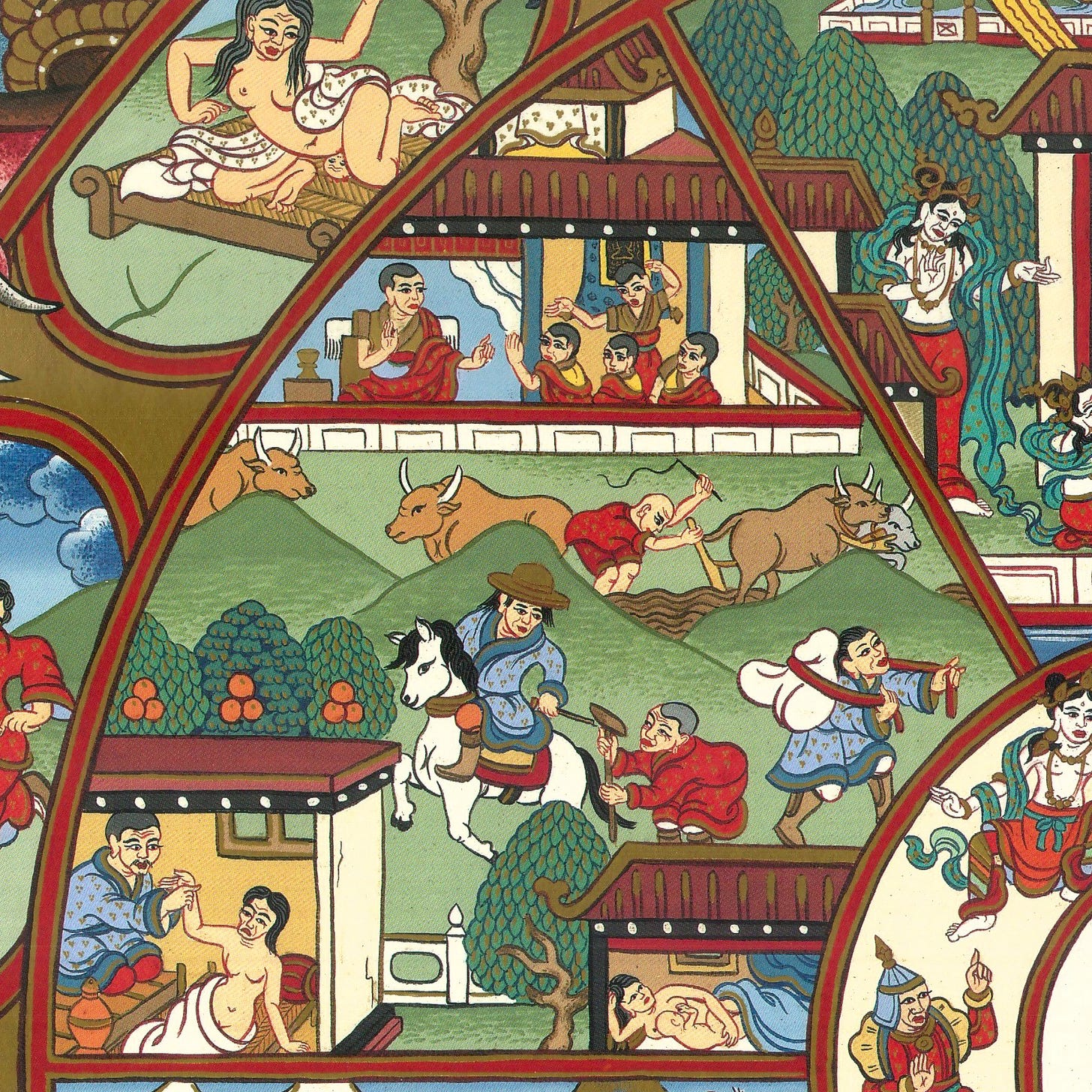

The vedanā skandha is the sensory, or sensing, component of the body-mind – referring to both the function of sensing and the data of sensation. As well as its more obvious 'external', or extraverted, function of perceiving our physical world, vedanā has a profoundly important 'internal' dimension. It is the function of mind by which we perceive the internal sensory space of the body – a profoundly important but neglected reality that was the focus of both the Buddha’s approach to spiritual practice, and Gendlin's Focusing, and which we can distinguish by referring to it as the domain of the somatic. Together, these functions of mind – the 'internal' and 'external' aspects of vedanā – tend to very strongly affirm our sense of separate selfhood. This sense of separation is at the core of that negative pole of human experience that the Buddha called dukkha – the suffering, or inherent unsatisfactoriness, of the human condition. Indeed, the Buddhist tradition tells us that our personalising identification with vedanā leads inevitably to a preoccupation with the personal body; with personal identity and social status; with personal achievement; with the accumulation of personal possessions and experiences; and with social difference and prestige – all of these being the characteristics of the archetypal Human Realm in Buddhism's 'Six Realms' cosmology.

The tradition speaks of the way our personalising identification with the vedanā skandha causes an accumulation of kleshas in a category that is called māna, which we can translate as 'pride', or even 'conceit', but which needs to be understood in terms of our all-too-human sense of separation – the existential isolation that the egoic mind creates because of the separation that is inherent in our identification with our physical bodies. When we learn to rest as Consciousness, and to become more familiar with our true nature, the vedanā skandha manifests in a new way. It becomes informed by what the Buddhist tradition came to call the Equalising Wisdom, and by the brahmavihāra of Appreciative Joy (muditā). Rather than highlighting our separateness, and the differences between us, the Equalising Wisdom highlights our common humanity and our connectedness with all of life.

The archetypal Human Realm in this context, is often compared with the other Realms and characterised as a very fortuitous place of rebirth because it is a Realm in which there is a balance of positive and negative experience – a balance that provides ideal conditions for gaining Enlightenment. When we see the Human Realm as a domain where the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha is the dominant perceptual function, we recognise what Buddhist tradition is telling us about one of the most important ways in which we lose our individuality and become immersed in a group identity. Our identification with the vedanā skandha is always, at the same time, an identification with various human group identities. We cannot separate out the social dimensions of the process by which our self-view is constructed – individual identity is always in some way socially constructed. The formation of identity is implicitly linked to the klesha category of māna, and to the various ways in which we are different and separate – the ways in which we are inferior or superior; accomplished or not accomplished; materially wealthy or materially poor.

So our identification with the vedanā skandha brings the particular sort of social self-obsession that we find pictured in the Human Realm – a way of being that is very focused on the various ways that our narrow experience of the body and the physical world affects the way we construct our social identity. The state of true individuality that the Buddhist tradition came to call Enlightenment however, involves a recognition of, and a transcendence of, this aspect of our conditioning – and frames that process of transcendence in terms of the brahmavihāra of Appreciative Joy, and the Equalising Wisdom.

I hope to show in the paragraphs below, that these two (Appreciative Joy, and the Equalising Wisdom) form an important pair of closely-related principles that together allow us to expand our perspective beyond scientific materialism and beyond a utilitarian and physicalist world-view that is over-focused on the physical body; the material world; and material accomplishments. Especially important is the 'internal' aspect of Appreciative Joy, which is a key doorway into the 'internal', or somatic aspect of vedanā, and to the experience of samādhi, or meditation. I hope also to show that Eugene Gendlin's Focusing practice is a profound support for Buddhist meditators, because it gives such detailed attention to the internal sensory space of the body – the domain of the 'internal', or 'somatic' aspect of the vedanā skandha.

In my previous article, I gave time to acknowledging the close connection between the Equalising Wisdom and the notion of Buddha Nature (Tathāgatagarba), which has an important place in the 'self-discovery' perspective of Vajrayāna Buddhism. The point made by the tathāgatagarbha teaching, and also by the trikāya doctrine more generally, is that our concrete and sensory world – the world of vedanā (and of the nirmānakāya level of the trikāya) – rests inseparably within the eternal dharmakāya. It is this universal and all-pervading presence of the dharmakāya that is equalising. The Equalising Wisdom highlights the paradoxically close relationship between the absolute sameness of the eternal dharmakāya level of mind (whose presence we can speak of in terms of Buddha Nature) and the absolute uniqueness of the true individual. Paradoxically, it is by dis-identifying from the superficial way in which the vedanā skandha constructs our identity, that we find our true uniqueness. The Equalising Wisdom allows us to find a human expression that is truely unique, and that, because it is rooted in the dharmic reality, is also characterised by an instinctive sense of connection and solidarity with all of humanity – and perhaps even all of life.

Some Buddhists express the concern that too much emphasis on the Equalising Wisdom leads to a bogus egalitarianism – a sentiment which would undermine the inherently and necessarily hierarchical nature of spiritual communities. We do indeed need to guard against reification in our thinking about the Equalising Wisdom, and the whole notion of spiritual development does indeed require us to accept that some people are more developed than others. There is however, an equally grave danger of reifying that idea into hierarchical and even elitist ways of thinking that undermine the foundational compassion of the Buddhist tradition. This is too big an area of discussion to go deeply into here, but it can be argued that the Equalising Wisdom provides an necessary counterpoint within our overall Dharmic perspective, without which we easily fall into a rigidly hierarchical ordering of our Buddhist social world – ways of thinking that the Buddha always sort to challenge.

Muditā – ‘Internal’ and ‘External’ Appreciative Joy

Through a process of dis-identification, the self-referencing tendency of the vedanā skandha has the potential to transform into the mutuality, solidarity, and humanitarianism of the Equalising Wisdom. It can become generously appreciative and empathetic, and appreciative in a completely non-acquisitive, non-attached way, sympathetically celebrating the achievements of others – indeed muditā is often translated as Sympathetic Joy. While Sympathetic Joy works to an extent, as a translation of the externally relational, or 'other-regarding', aspect of muditā, Appreciative Joy works better for the very important receptive, or 'self-regarding' aspect of muditā, which is foundational for meditation practice.

When I first learned about the brahmavihāras, I was taught to translate muditā as Sympathetic Joy, so I do not suggest this different translation lightly. For me however, the idea that there is an unconditioned inner joy – an inner Appreciative Joy that we can access regardless of external circumstances – is central to the Buddha's message. The more relational, extraverted and externally appreciative aspect of mudita is, of course, hugely important, but the use of 'Sympathetic Joy' for both the 'internal' ('self-regarding') and 'external' ('other-regarding') aspects of muditā, has the potential to create confusion within this sublime teaching. Thankfully, I am not alone in thinking in this way – most Buddhists who practice all of the brahmavihāras regularly, come to the same position.

For brevity, I have been forced to skirt over some of the differences between the 'internal' and 'external' aspects of the rūpa and samjñā skandhas and their corresponding brahmavihāras, but in regard to vedanā, the distinction needs to be highlighted, since the difficult-to-define receptive and self-appreciative attention of 'self-regarding' muditā plays such an important role in our Mindfulness of the 'internal' aspect of vedanā, and is so very important to the deepening of our practice of samādhi. I also need to address the more generally important pattern of close connections that I have been highlighting between the 'internal' and 'external' aspects of rūpa, samjñā, vedanā, and samskaras, and the corresponding 'self-regarding' and 'other-regarding' aspects of upekshā (Equanimity), mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness), muditā (Appreciative Joy), and karunā (Compassion). When we recognise the connection between the four 'internal' skandhas and the corresponding 'self-regarding' brahmavihāras that unfold out of them, we are also called to recognise how very limited and limiting is the language of 'self-regarding' in this context. Clearly this way of talking represents a very crude conceptualisation, since the four 'self-regarding' brahmavihāras, once they are explored deeply are found to involve a receptivity, or Other Power orientation, towards the mahabrahmavihāras – the sources of the brahmavihāras on the dharmic level of mind.

As we move from a 'self-development' or 'self-power' mode of practice, to one that may be better characterised in terms of a 'self-surrender', or Other Power, perspective, we encounter this need to redefine our terms. Attending precisely to the words that we use to name these Dharmic principles is important. Indeed, our recognition of the semantic limitations of our words is an important aspect of our growing awareness of the reifying and limiting activity of the rūpa skandha. Once we go further still in our practice and incorporate a 'self-discovery' perspective, we are even more keenly aware of the limitations of language, and of the way in which the egoic mind rests on dualistic assumptions that are patterned into our thinking and our forms of speech.

While I have become keenly aware that this term 'self-regarding' is conceptually incorrect and ultimately extremely limiting, I have continued to use it much of the time – always in single inverted commas (i.e. 'self-regarding') – aware that this is the terminology used by most practitioners of the brahmavihāras. I do however, feel a strong need to challenge the use of the term 'self-regarding' in regard to the receptive, or Other Power experience of the brahmavihāras, and will sometimes simply use 'internal' or ‘inner’ instead, since this is the terminology used in the English translations of the Pali canon in connection to the corresponding skandhas and Foundations of Mindfulness.

Carl Jung's very precise and deeply explanatory term 'introverted' is another possible translation in all three of these contexts, but I have generally stayed with 'internal', since the meaning of the term 'introverted' is not well understood. My wish is that my readers will recognise that I am using the terms 'self-regarding' and 'internal' with an awareness of their limitations in this context. In connection with the 'self-regarding' brahmavihāras, the word 'internal' is clearly also inadequate, since it does not begin to express the profundity of the practitioner's sense of revelation as they enter into an Other Power mode of practice – recognising, with a sense of wonder, that they are coming into relationship with the benevolent and beneficial dharmic reality of the mahabrahmavihāras. It would seem that we are already beginning to reach the limits of language when we enter the transition into that Other Power phase of the path that we call 'self-surrender'.

To understand all this better we need to understand that in meditation practice, the transcendental dharmic reality is felt to have the qualities of the mahabrahmavihāras – the 'great' brahmavihāras. Of these qualities, the easiest to recognise and name are the primordial stillness (upekshā); the primordial love (mettā/maitri); and the primordial compassion (karunā). More subtle and difficult to name is the fact that the dharmic reality is experienced as primordially generous, and as a primordial abundance that is always overflowing into more and more concrete and tangible levels of emanation – eventually finding expression in this concrete physical world of which we are part. The tradition tells us that the benevolent, beneficent and beneficial dharmic reality pervades the universe completely equally and evenly, so that everyone is touched by the generosity of its blessing, and so that every last human being receives the gift of Consciousness – and therefore also receives the great gift of Buddha Nature, the indwelling potential for Enlightenment. When, either in the experience of samādhi (meditation) or, in our wanderings through the wonderland that is planet Earth, we experience this sense of the universal blessing, and perhaps also a sense of the extraordinary particular blessing of having encountered the Dharma, we experience muditā – we experience the 'internal', receptive, or 'self-regarding' aspect of muditā, which is Appreciative Joy.

When the appreciation of muditā is extraverted and externally relational, and directed toward people in our lives, we can sometimes call it Sympathetic Joy, if we prefer that translation. Sympathetic Joy communicates a quality of self-lessness, non-attachment and non-envy in our appreciation of those who are blessed and who have achieved much in their lives. Our appreciative and celebratory response to them includes a sympathy – we are feeling with them in their achievement. It is usually helpful however, to recognise that the base note of the refined emotional response that the Buddhist tradition calls muditā, is Appreciative Joy – we ourselves feel blessed and grateful when we witness the wonderful qualities and accomplishments of others.

I have been emphasising the fact that the brahmavihāras, while they profoundly affect the quality of all the relationships in our personal lives, ultimately arise from the dharmic reality, and are therefore in a sense non-personal. In my experience, people go deeper in their practice if they allow themselves to think of the brahmavihāras as emanations, or reflections, or resonances, in our world of separation, of the higher, non-personal reality of the mahabrahmavihāras. If we turn towards the dharmic reality consistently in this Other Power way, the impact that the mahabrahmavihāras have on our personal lives can be vast.

Gratitude and Appreciative Joy

One of the profound ways in which muditā finds expression in our personal lives is in our experience of, and practice of, Gratitude – an emotional response that is very close to Appreciative Joy, but more personal and specific. The recognition that Gratitude is a dimension of muditā, is important because it highlights the connection with the concrete, sensory and practical skandha of vedanā – the skandha of the physical, and of somatic embodiment. As a starting point, in distinguishing Appreciative Joy and Gratitude, we can say that Appreciative Joy is more general and impersonal, whereas Gratitude is more specific and personal. When we are grateful we are acknowledging the very particular benefit of something that we are receiving, or have received. While our needs are always universal and in some sense impersonal (shared with the rest of humanity), the specific way in which our needs are met brings a specific response of Gratitude – which can nevertheless be recognised as ultimately non-personal.

Another way in which we can distinguish these two interconnected aspects of muditā, is to say that Appreciative Joy is the foundation for Gratitude – that it flows into Gratitude and finds expression in Gratitude. We can sometimes be appreciative without expressing Gratitude, since Gratitude is in some sense a personality quality and language skill that needs conscious development. By learning to find words for our Gratitude and Appreciative Joy, we deepen our connection with both of them, and we deepen our connection with muditā. Indeed, expressing Appreciative Joy, whether generally, or as Gratitude in the context of a particular relationship, is a powerful creative act. It not only positively impacts the quality of our relationships; it transforms our energetic relationship with self and world – since it opens us energetically to the life-energy of our true needs and to a deeper awareness of what specifically meets those needs in our own life context.

Much more could be said about Appreciative Joy and the powerful way in which it functions in concert with each of the other brahmavihāras. In a future essay, I would also very much like to write about the way each of the brahmavihāras needs to be recognised as finding expression in our lives through a process of emanation. Emanation is a translation of an ancient Greek word that is used frequently in the context of Platonic thought, and which I shall be outlining in more detail in my next article. Like the notion of hermetic relationship that I mentioned earlier, emanation is a word that allows us to think in an Other Power way – and about the way in which the same archetypal principle can manifest in 'higher' and 'lower' ways, and in progressively more concrete forms of embodiment. So muditā finds expression in our personal lives and personalities because it exists a priori as a dimension of the dharmic reality. The brahmavihāras exist as the mahabrahmavihāras prior to our experience of a resonance of them in our minds in the context of our meditation practice – but they then continue to emanate, finding expression more and more concretely in our personal psychological attitudes and our personal communication skills.

There is a whole body of study and practice that explores the details of this emanation process by which we manifest the brahmavihāras in the specifics of our day-to-day communication and the particular forms of our language. While the late Marshall Rosenberg would not have referred to the brahmavihāras as such, he was aware that, through his Nonviolent Communication (NVC) model, he was teaching people to unlearn their egoic conditioning and to return to their deeper instinctive humanity, compassion, and emotional intelligence. Marshall Rosenberg's NVC is doubly relevant in this context because his work, not only comes out of the same Humanistic Psychology stable as Gendlin's Focusing, but shares Gendlin's conviction that the transformation of personality that Buddhism might call Positive Emotion, springs from a deep commitment to meditative self-enquiry – from the self-healing and self-connection process that Rosenberg called 'self-empathy', which is almost identical to Gendlin's Focusing.

Clearly these ideas are deeply relevant and powerfully supportive of both Buddhist practice and Gendlin's Focusing. I have referred to Marshall Rosenberg's model frequently in my articles, but would very much like to write more. Another related model that may be regarded as describing a process of turning towards a source of objectivity within, is Sociocracy – in that instance we seek to go beyond the egoic mind in order to achieve efficient and effective collaborative creativity and group decision-making. Wherever we apply it, the logic of the 'self-discovery' approach brings a depth to our various personal development practices, and the skills of objective reflection and evaluative discernment that we learn through Gendlin's Focusing bring a subtlety, refinement and deep intelligence to every aspect of our relating and creative engagement with life.

It is important, in my view, to acknowledge that the four brahmavihāras – perhaps better thought of as the eight brahmavihāras – when we consider that each one has an 'internal', or 'self-regarding' aspect and an 'external' and 'other-regarding' aspect, together present a complete and comprehensive model of Positive Emotion. If we fail to recognise that Appreciation is inherent in muditā, we find ourselves needing to introduce it as a separate dimension of Positive Emotion. When we do this – treating Appreciation as if it were a fifth component of Positive Emotion in addition to the four brahmavihāras, this has the effect of breaking the beautiful mandala-symmetry and archetypal pattern of the ancient Indian model. I take the view, that we need to deeply explore the Dharmic model that the Buddhist tradition has blessed us with, before we start finding it wanting and modifying it.

Ratnasambhava and Māmaki

In the sambhogakāya mandala, the 'other-regarding' and 'self-regarding' aspects of muditā, are found symbolised in the southern quadrant and personified by the figures of Ratnasambhava and Māmaki. The cultivation of the 'internal' and 'external' aspects of the Equalising Wisdom and the appreciative sensibility, are beautifully expressed in Eugene Gendlin's practice of attending to the 'felt-sense'. Gendlin used the term 'felt-sense' to describe the complexity and beauty of the bodily-felt experience and of the somatic imagery, that emerge when we attend to the actual phenomenological sensation of those felt-experiences that we often refer to, rather vaguely, as 'feelings'. He emphasised that a felt sense is a holistic phenomenon. In Buddhist terms we can think of the felt-sense as holistic because, while we might initially discover it as a form of sensation (vedanā) in the field of the body, we find as we attend to it, that it has an image quality (James Hillman called it an 'image-sense'), and that it has the other cognitive-perceptual skandha components woven into it – the evaluative dimension of samjñā; the volitional dimension of the samskāras; and the descriptive, or 'point of view' dimension that is rūpa.

The translation of the sensory or 'sensing' perceptual function of vedanā as 'feeling' is understandable, but is terribly problematic, in my view – as I have tried to explain above. It leads to a disastrous confusion within the whole skandhas model because the word 'feeling' is the English verb for the act of subjective evaluation, or non-logical discernment, and includes emotional responses in general. One of the reasons that the skandhas model has such great explanatory power as a cognitive-perceptual model, and as a framework for Mindfulness and self-enquiry, is precisely because it separates the perceptual act of sensing or sensation, from the cognitive act of evaluation. By translating vedanā as 'feeling' – a word that has both sensing and evaluative connotations in English usage – we fundamentally undermine one of the main intentions of the Buddha's model.

In my view, 'sensing' is a much better word for the vedanā skandha. For clarity, we would do better without the evaluative connotation that is present in the word 'feeling'. 'Sensing' works better precisely because it is a word (a verb) that connotes, the non-evaluative sensing process that takes place prior to the evaluative process that in English we call 'feeling', and that we call samjñā in Sanskrit. The word 'feeling' is doubly confusing as a translation of vedanā. When it is understood as a verb, it brings, as I have explained, the connotation of active evaluation, which is the domain of samjñā, when we really need a word that communicates the simple act of non-evaluative sensing.

When 'feeling' is used as our translation of vedanā however, people tend to also use it as if it were a noun. This is profoundly undermining to our understanding of the Buddha's skandhas model, which is, after all, trying to challenge our tendency to reify our experience. The intention of the Buddha in his adoption and adaption of the ancient Indian skandhas model was to turn the nouns into verbs – to turn the fixed 'things' in the original model into the cognitive-perceptual processes that we find set out by the Buddha in the Pali canon. His intention was to subvert the original vedic model, presenting it in a new dynamic and systemic style of language – an action language, or process language, in which verbs replace the static, concretising language of nouns.

In English, we use the word 'feeling' for the extremely subtle act of subjective evaluative discrimination, while also using it to describe the more concrete act of sensing sensations via the external bodily senses, and more subtly via our sense of the vague 'cloud of sensations' in the internal space of the body. Making matters worse, we have the common use of 'feeling' as a noun that describes a collection of categories of 'feelings'. Furthermore, this use of the noun 'feeling' as in 'I have a feeling of anger' leads us to the rather crude habit of labelling bodily-felt evaluative responses and placing them in conventionally understood categories. Hence an English-speaking person will say that they have a feeling of annoyance, or a feeling of love, or a feeling of appreciation, or a feeling of fear – all of these expressions being essentially evaluative, and very lacking in the sort of linguistic and phenomenological specificity that Gendlin's urged us to find in our description of bodily-felt experience. From the phenomenological point of view of Gendlin, or of the Buddhist tradition, this form of language is not only phenomenologically inaccurate – it also tends to both conflate and reduce our processes of bodily-felt sensation and evaluative response to fixed 'things'. In the context of Mindfulness practice and the intimacy of spiritual friendship, we also become aware that it constitutes a terrible reduction of our rich, unique and personal evaluative response processes, to always place them in the conventional 'feeling' categories that our language affords us – however much this may be necessary for brevity in ordinary communication.

Whenever we think of a feeling as a thing, and label 'feelings' with nouns, we are working against the intention of the Buddha's 'empty' skandhas model of mind. Gendlin showed us that, in reality, that 'thing' that we label as 'a feeling', and place in a conventional category, is always a unique and particular felt-sense process. Each so-called 'feeling' is actually a felt-sense – a complex process of evaluative discrimination or discernment waiting to unfold its perception to the extent that we are willing to pay attention to it. While our entry into a felt-sense is very often through the act of sensing inwardly (‘internal’ vedanā), it is very much more than a sensation. Rather it is a complex wholistic body-sense in which all four of the cognitive-perceptual functions of Consciousness come together – an objectifying conceptualisation, or point of view (rūpa); an experience of bodily sensation (vedanā); an evaluative response charged by conscious or unconscious memory (samjñā); and one or more volitional energies (samskāras). These elements are all tangled together within the system of the egoic mind until we begin to tease out the strands through Mindfulness practice.

Each of the skandha components of mind, function very differently in the context of Mindfulness – very differently when they are conscious and differentiated, than when we are unconsciously identified with them. There is great value in recognising that the Tibetan 'mandala wisdom' provides us with a hermetic structure by which we can see the archetypal correspondences between the dimensions of the egoic mind and the corresponding dimensions of our experience of the dharmic reality. Within the framework of the mandala, Mindfulness can unfold either as a cyclical sequence (the clockwise sequence of the four quadrants of the mandala), or as processes of reconciliation within the two pairs of opposites – the two axes of the mandala. The mandala shows multiple polarities which are similar in some way, and hermetically related. The principles that are represented at opposite ends of the mandala axes, are polarities of a different sort – what we might call true opposites. The mandala wisdom offers an understanding of how these opposites relate to each other, and complement each other, and how they can ultimately be integrated and reconciled through meditative practice.

Buddhist wisdom invites us to distinguish the sensory (vedanā); evaluative (samjñā); volitional (samskaras); and describing-objectifying (rūpa) functions of mind, and the point of entry in this practice is generally to engage in meditative attention towards our internal felt experience of sensation (vedanā) in the field of the body. By attending to this 'internal' aspect of vedanā – and being willing to be phenomenologically accurate in our description of our actual sensations in the internal field of the body, we resist the temptation to merely label our mental and emotional experience with the common 'feeling' words (nouns) that are the conventional categories of evaluative reaction. This discipline can be difficult to establish, but when we do manage to distinguish vedanā (sensing, or sensation) and samjñā (evaluation) from each other, our experience of the body-mind becomes much more differentiated, and we become much more Mindful in these domains. Most significantly, these subtle perceptions and cognitions then become 'un-fixed' – they are revealed to be dynamic and ever-changing processes.

The term Focusing was a metaphor from photography – since the act of attention that Gendlin called Focusing is like bringing a fuzzy photographic image patiently into focus. For Gendlin, the act of sensing (vedanā) the complex texture of our internal experience is foundational – for him it was the humble and humbling doorway into the mystery of real emotional transformation and deep personality change. In the early Buddhist formulation of 'conditioned co-production' we find the same emphasis on sensation (vedanā) – as the doorway into the core practice of distinguishing the sensory, evaluative, and volitional components of felt-experience within the body-mind. So Gendlin was very like the Buddha in the way he took bodily-felt experience to be our point of entry into profound personality change and wisdom.

As Western Buddhists we need to keep reminding ourselves that the Buddha's practice of samādhi (meditation) is a body-mind practice. As my regular readers will have noticed, I use the terms ‘mind’ and ‘body-mind’ interchangeably. All of our thoughts have felt-senses that go with them, and when we manage to empty the mind of thought, there are always subtle felt-senses that remain – the difficult-to-describe felt-senses that we call Equanimity and Being, and the other brahmavihāras. The Buddha, ascending easily as he did, through the four foundational states of Integration that he called the four rūpa dhyānas, used to share felt-sense images with his students, to describe what he was experiencing in as phenomenologically accurate a way as he could.

I shall be describing the Buddha's felt-sense images of the four rūpa dhyānas in detail later in this series of articles. I believe they provide a wonderful example of how vedanā unfolds as we engage deeply with it. Through meditation practice vedanā becomes, in the terms of Sangharakshita's 'System of Practice', our point of entry into the experience of Integration, Positive Emotion, Spiritual Death and Spiritual Rebirth. In the Buddha's rūpa dhyāna images we clearly see him describing what Eugene Gendlin would call a series of felt-senses.

While the Buddha's rūpa dhyanā images appear to be universal, so that a modern practitioners can recognise the Buddhas's felt-senses in their own process, most of the felt-senses that we encounter when we learn Focusing are somewhat different, since they are unique and infinitely various. Logically, it would seem that the Buddha's rūpa dhyāna images need to be thought of as images of our encounter with, and integration of, dimensions of the dharmic reality. While we can also experience these felt-senses if we choose to cultivate a relationship with the dharmic reality, most of our felt-senses are those of parts of the egoic mind – each one a manifestation of a process within the body-mind that is moving towards Integration and Positive Emotion; moving towards healing. What is perhaps most striking and useful about the Buddha's four felt-sense images that have come down to us in the Pali canon, is the fact that we can use them as guidance in our own integration process.

© William Roy Parker

Consider reading the next article in the Buddha Meets Gendlin series:

10. The Brahmavihāra of Compassion

In Buddhist thought, the volitional aspect of Positive Emotion is called karunā, or Compassion, but this word also translates into the important English word Empathy – that intuitive aspect of Positive Emotion, without which Compassion cannot be understood and cultivated. Given the absolute centrality of Compassion in Buddhist thought, there is sometime…