4. The Inner Path of Ethics

Acknowledging the archetypal tendencies of the egoic mind, while opening to the resonance of the 'dharmic' reality.

Many of the reflections that I find myself wanting to share here, may not appear obviously connected to Gendlin’s Focusing model. The connections that I am making here, in regard to the 'mandala wisdom' – the archetypal psychology of Tibetan Vajrayāna Buddhism, that is attributed to the great Padmasambhava – are however, either discoveries made during my years practicing Focusing, or were powerfully reinforced by that period of regular Focusing practice. The depth and the detailed nature of the self-enquiry that I am advocating here, is also something that I learned during my years of Focusing practice.

For me, there is a further dimension to the value of the psychology of Vajrayana Buddhism to students of Gendlin’s Focusing. The psychology of the Five Wisdoms mandala is a rich archetypal psychology which is communicated in a language of colour, Element symbolism, and mythic imagery. This is the language of ‘felt-senses’ and ‘image-senses’ with which the body speaks to us in the Focusing process from beyond the egoic mind. Furthermore, it is a psychology that has the transcendental dharmic reality as its core, so it provides a psychological frame of reference that has a life-serving openness and spiritual depth that reflects the nature of Focusing processes. Our experience of Focusing, like our experience of meditation, is profoundly affected by our conceptual framing of it. By framing Focusing within the ‘mandala wisdom’ psychology of Vajrayāna Buddhism, we allow the extraordinary depth of possibility that is inherent in that practice to be fully expressed.

This article is the fourth article in my ‘Buddha meets Gendlin’ series. The first article in the series is Eugene Gendlin's 'Clear Space' and the previous article in the series is Form is Only Emptiness.

The Middle Way beyond Eternalism and Nihilism

The early Buddhist tradition presented mind in terms of the dichotomies of samsāra and nirvāna. The later introduction of a third, intermediate level, into the way mind was conceptualised – the notion of a sambhogakāya as the middle level in a three-fold, or trikāya, model of mind – had the effect of opening up Buddhist philosophy and culture to the way the unknowable, and entirely unconditioned dharmakāya level of mind finds expression in the body-mind of the practitioner as archetypal imagery and non-egoic somatic experience. The 'empty' sambhogakāya gives us a way of talking about encounters with archetypal personifications and suprapersonal forces, without personalising or reifying those experiences.

There is a common misunderstanding that arises from an incorrect conceptualisation of the Buddha's description of his path of practice and philosophy as a Middle Way. While Gautama Buddha does indeed urge his students to avoid the extremes of 'nihilism' and 'eternalism', what he means by this invitation is subtle and nuanced. He is saying that we should avoid both the error of any view that holds that the self is permanent, unchanging, and everlasting; and the error of any view that sees the self and world as devoid of an eternal or unconditioned dimension. The Buddha was not denying the existence of that 'empty', unconditioned, and unknowable dimension of mind which became known as the dharmakāya, and for which I have been using the epithet 'eternal'.

This is why I like to use that word 'eternal' – it is a poetic epithet that serves to express the nature of that 'empty' unknowable, unconditioned reality that the Buddha was pointing to when he spoke of nirvāna. In the modern Westernised world, there is a very much greater danger of practitioners falling into forms of nihilism. Indeed a great many Western Buddhists are in fact nihilists, in terms of Buddhist philosophy. What I am saying is not as provocative as it seems. I am just saying that it is a feature of modernity that scientifically-educated people find it difficult to believe in a transcendental reality, and Western Buddhists are often well-adapted, consciously or unconsciously, to the nihilism of the prevailing cultural world-view. So they may not believe in a dharmic, or transcendental reality – or at least they may not have adequate conceptualisations to point to such a reality with conviction. They also may not have a way of talking about the agency of that transcendental reality in their lives – fearing that this might imply a belief in some form of interventionist deity like the Christian 'God'.

It is understandable that Westerners, heirs to the science and the philosophical and political freedoms of that revolutionary cultural process that we call the European Enlightenment, might reject traditional Buddhist notions of a beneficent transcendental reality – even if that transcendental reality is 'empty'. I take the view that, as Western students of Buddhism, we need to be especially careful to guard against this nihilistic cultural conditioning in ourselves. Indeed, I believe Western Buddhism can offer a way out of this dilemma – I believe it can offer a world-view that has scientific rigour, while also offering a keen sense of the ever-present beneficial reality of a transcendental dharmic dimension.

The Buddhist tradition evolved because it was a tradition of meditators and mystics – meditators and mystics who were also thinkers and teachers, but were primarily meditators, and therefore grounded in their bodily-felt experience. They were meditators who took the Pali Canon as their starting point, but who were also always endeavouring to find fresh ways of describing their mystical experience – of describing the indescribable. The trikāya doctrine was a pragmatic development within this challenging project, and represented a huge step forward conceptually. So, the imagery and symbolism of the sambhogakāya mandala depicts for us the eternal benevolence of the dharmic reality; ever present, and felt within us as a somatic resonance – as bodily-felt experience.

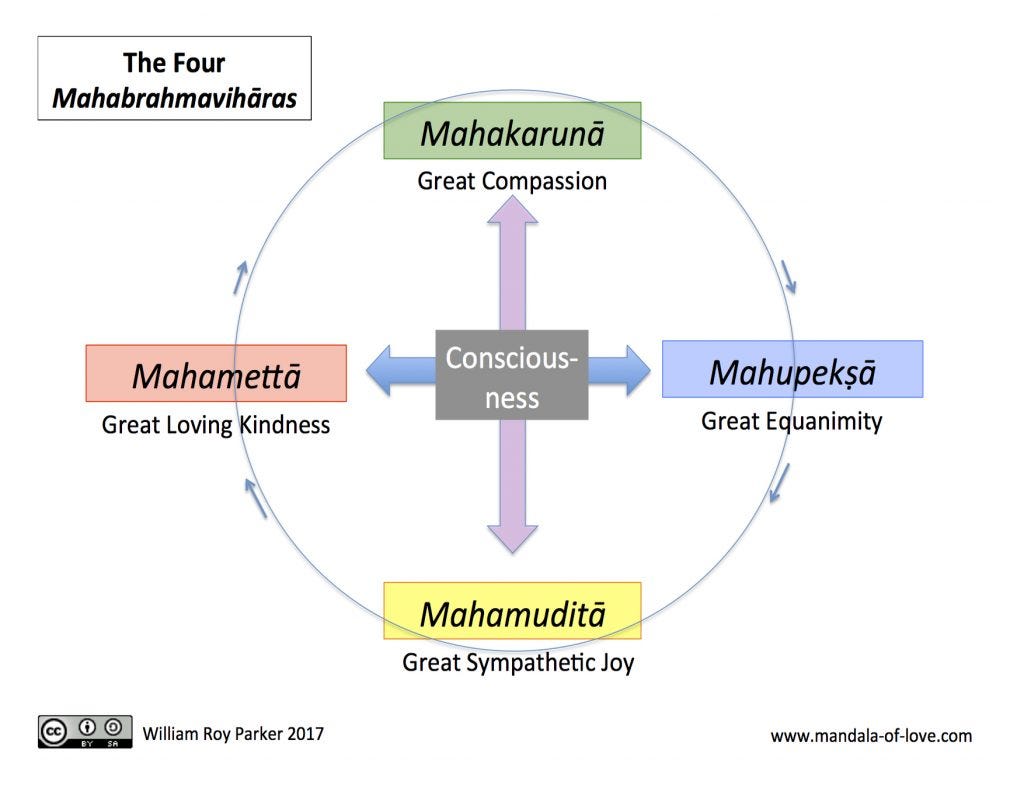

Gendlin’s method was utterly experiential – avoiding metaphysics and employing the minimum of conceptualisation about the nature of mind. When, as Buddhist practitioners however, we apply Gendlin's phenomenological method in our approach to the body-mind, we find it profoundly affirming of the trikāya view. The trikāya is a metaphysical description of mind, but it is not a departure from experience. Rather it is an affirmation of our experience. I find it profoundly affirming of my experience to think of the ten Buddha mandala of the sambhogakāya as a reflection of the dharmakāya in the sambhogakāya level of mind. It allows us to recognise that both the 'clear space' of Consciousness, and the traditional four dimensions of Positive Emotion (the brahmavihāras) are a given – that they are inherent in the nature of mind at the level of the sambhogakāya. So, while the outer-inner pairing of Vairocana and Ākāshadhāteshvari provide us with an archetypal personification of Consciousness, the other four 'Buddha couples' provide similar archetypal personifications of the pairs of positive emotional 'attitudes of Consciousness' that we call the brahmavihāras.

One of the ways in which we rescue the sambhogakāya mandala from abstraction is by making the correct associations between the archetypal Buddhas and the corresponding brahmavihāras – I have set these out in my previous article, and shall be explaining them further below. Far from being abstractions, the brahmavihāras are our guide on the path to the bodily-felt experience of Integration and Positive Emotion. They are, quite literally, the somatically-felt experience of the transcendental dharmic reality. They are foundational also, because they provide the key, in my view, to our development of that deep ethical sensibility that is the foundation of the Dharma life. In the Mahayana Buddhist tradition the practice of the four brahmavihāras came to be regarded as absolutely foundational on the path of the bodhisattva – absolutely essential for our recognition of, and surrender to, the bodhicitta, the transcendental altruism that fills people with a wish to serve the wellbeing and spiritual upliftment of all beings.

Cultivating Ethical Sensibility – the Outer and Inner Paths

If we undertake only a superficial study of Buddhism, we can be forgiven for seeing the Buddhist cultivation of an ethical sensibility as founded merely on adherence to the five traditional behavioural Precepts – non-harm; non-stealing; refraining from false and harmful speech; refraining from sexual misconduct; and refraining from intoxication. Clearly, this five-fold behavioural framework provides a necessary moral foundation, and serves to restrain the worst tendencies of the egoic mind – basic ethical principles that can be embraced by all, including non-meditators. Our focus on behavioural precepts, and on taking such precepts as the foundation for how we think about ethics, tends to lead to an emphasis in our presentation of Buddhist ethics that is external and behavioural rather than internal and spiritual – a worthy approach, but one based on rules and principles and external moral codes. The Buddhist practice of ethics is inseparably connected with our practice of meditation and self-enquiry.

Both brahmavihāras practice, and Focusing practice, take us much deeper into our ethics practice. The ethical perspective they bring, can be characterised in terms of the Western philosophical tradition as close to the framing of ethics within the Platonic/Neoplatonic approach – which involves a recognition of the way that the ultimate nature of Goodness and Wisdom (which is very much akin to the dharmic reality of the dharmakāya and sambhogakāya in Buddhist tradition), naturally wants to find expression, or 'emanation', in the human mind. Ultimately, Buddhism shares this view, asserting that ethical behaviour is a natural expression of our deepest true nature, and that to behave unethically is a sort of violation of our being – a violation in which we cut ourselves off from, or go against, who we ultimately are. Since the brahmavihāras are Buddhism's description of the dimensions of love in the depth of the mind, they provide us with the basis for a deep and life-long process of 'self-discovery', and for a process in which we familiarise ourselves with the intangible and transcendental source of that ethical intelligence and love that exists within us, but entirely beyond the egoic mind's tendencies towards greed, hatred, delusion, envy, and pride.

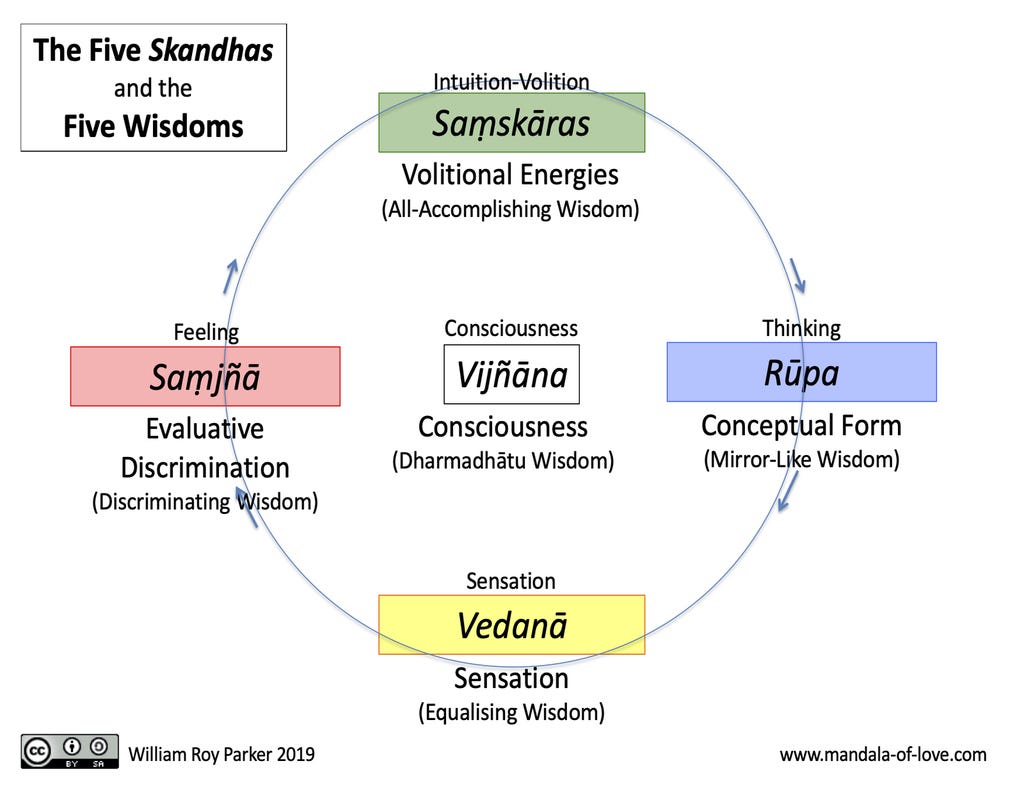

These five karmic areas of blunted or absent ethical sensibility are directly related to the five cognitive-perceptual skandhas (as I shall be explaining below), and are known in Tibetan Buddhist tradition as the five kleshas – variously translated as the 'obscurations' or the 'defilements'. In early Buddhism there appears to been a focus on only three of the klesha categories – greed, hatred and ignorance – but in later centuries there were several longer lists. I regard the five-fold list, that was presented to us by Padmasambhava in the Bardo Thodol, as by far the most useful. It has a profound logic through its close association with the Buddha's five skandhas teaching.

This powerful and comprehensive five-fold system is a later development within Buddhist history, that is nevertheless rooted in the Buddhas teachings on the five skandhas; the five Spiritual Faculties; and the corresponding Foundations of Mindfulness. Theravada Buddhists are however, sometimes unaware of the correspondences between the five skandhas and the five kleshas, so I shall share them briefly here. The idea that the apparent emotional negativity and psychological inertia of the egoic mind is inherent in the cognitive-perceptual structure of the body-mind is a foundational one for the Buddhist tradition.

The late Eugene Gendlin shared the Buddha's wish that we should step out of this egoic stuckness and negativity through the practice of Mindfulness, by resting as the 'clear space' of Consciousness. Focusing, like meditation and Buddhist Mindfulness practice, allows us to familiarise ourselves with a creative and open way of being, and with the brahmavihāra attitudes of mind that allow us to heal and evolve – to undergo personality change. I hope to show how skandhas, kleshas and brahmavihāras are archetypally (or 'hermetically') linked, but we should first establish some clarity about the way the cognitive-perceptual functions of Consciousness (skandhas) lead to contractive and defensive emotional patterns (kleshas), and to the associated negative group behaviours that are suggested by the corresponding Realms of Buddhist tradition. These correspondences are set out particularly clearly in the rich and colourful imagery of the Bardo Thodol texts.

The skandhas, kleshas, and Realms

Here, very briefly, is what the tradition tells us about the connection between the skandhas, kleshas, and Realms:

Firstly, we are told that through our unconscious and undifferentiated identification with the vijñāna skandha (Consciousness), which the Buddhist tradition calls avidyā (spiritual ignorance), we cut ourselves off from the instinctive altruism of the bodhicitta, and from the ultimate liberation of Enlightenment for the sake of all beings, even though we may have consistently attained access to those refined and positive dhyānic states of consciousness that Buddhist tradition speaks of in terms of the Deva Realms. This is a very important distinction that the Buddhist tradition makes: that devas, the Gods of pre-Buddhist tradition, are very different from the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, since they a caught in subtle but very fixed, and ultimately narcissistic, forms of egoic identification that is said to have the character of 'spiritual ignorance' (avidyā).

Secondly, we are told that an unconscious and undifferentiated identification with the objectifying and ‘form-creating’ rūpa skandha, through its creation of judgemental and divisive conceptualisations and narratives, leads to an accumulation of kleshas in the category of dvesha (hatred) – the klesha that characterises the Hell Realms.

Thirdly, we are told that an unconscious identification with the evaluative samjñā skandha, through its undifferentiated attention to subjective states related to emotional memory, leads to an accumulation of kleshas in the category of rāga (craving) – the klesha that characterises the Preta Realm.

Fourthly, we are told that an unconscious and undifferentiated identification with the intuitive and volitional samskāras skandha, leads us to be powerfully motivated by envious and mimetic (i.e. imitative) desires that are unrelated to our real needs, or the needs of others – and to an accumulation of what the Buddhist tradition calls the kleshas of irshya (envy), the klesha category that characterises the Asura Realm.

Fifthly, we are told that an unconscious and undifferentiated identification with the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha, through its preoccupation with, personal experience, with the personal aspects of the body, with personal possessions, with personal identity, and with personal achievements and skills, leads to an accumulation of kleshas in the category of māna (pride) – the klesha that characterises the Human Realm.

These five categories of kleshas can be thought of as energetic layers in the way the egoic mind is somatically embodied. Focusing practice, because it invites us to attend to the actual complexity of our somatic experience, can help us to see the Buddhist notion of the kleshas in a way that is richer and much more experiential and phenomenologically true. While we may continue to recognise the skandhas and kleshas in our felt experience, we notice how they are usually combined into constellations of felt experience that have the character of 'selves' – selves, or sub-personalities, or 'psychological parts', which we are no longer identified with.

The Skandhas as the Components of Psychological Parts

Each of these psychological parts, when investigated closely, is seen to have the characteristics of the skandhas and kleshas. The skandhas show themselves as the components, or attitudes, of each psychological part: Firstly there is the psychological part’s ‘point of view’, or description of what is happening (rūpa skandha), and its judgemental mental reactivity towards self or world (the klesha of dvesha). Secondly, there is the very particular experience of the sensory embodiment (vedanā skandha) of the psychological part – an embodiment that expresses separateness and personalisation (the klesha of māna). Thirdly, there is an evaluative reaction based on the emotional history (samjñā skandha) of the psychological part – an evaluative reactivity that tends to locate the possibility of love and wellbeing in external persons, objects and experiences (the klesha of rāga). Fourthly, there is a volitional reaction of not wanting or wanting (samskāras skandha) that expresses impulses for control in order to manage the unconscious fear bred by envious desire (the klesha of irshya). When we engage with psychological parts in the meditative self-enquiry of Focusing, all the skandhas and kleshas may be observed to be present in some form – but so also, if we are choosing to familiarise ourselves with Presence, are the brahmavihāras.

In future articles in this series, I shall be going deeper into the question of how the skandhas, kleshas and brahmavihāras are located in the body. There is a Tibetan Buddhist understanding in this regard that I have found very useful. This acknowledgement that personality change happens 'in the body', like a meditative process, as a bodily-felt energetic shift, is integral the Gendlin's Focusing practice. The Buddhist tradition shares with Gendlin the wish to understand how the skandha and klesha components that give rise to the appearance of a self, are energetically accumulated and held in the body. Buddhism goes further however, because it seeks to understand how the dharmic reality is also embodied within us. Just as the categories of kleshas can be imagined as energetic layers in the somatic field of the body, so too can we imagine the brahmavihāras as energetic resonances within the same layers – becoming revealed more clearly as identification with the egoic kleshas is progressively released.

The ‘Great’ Brahmavihāras

From this Tibetan 'self-discovery' perspective, the cultivation of the brahmavihāras may be partly characterised as a process in which we learn to attend to the resonance of the mahabrahmavihāras (the 'great' brahmavihāras) – the energetic resonance of the sambhogakāya felt as vedanā (sensation) in layers of the body's somatic anatomy. The Tibetan Buddhist tradition helps us in this endeavour, by inviting us to be aware of the chakras – the points on the centreline of the body where the resonance of the mahabrahmavihāras may be most keenly felt. One of the curious, but perhaps not surprising, parallels between Buddhist meditation and Focusing, is this invitation to pay particular attention to felt experience on the centreline of the body. The felt processes that Focusing practitioners describe are often experienced to be happening at what Indian tradition would identify as the chakra locations – especially those in the trunk of the body up to the level of the heart.

In my experience the experiential locations of the resonances of the mahabrahmavihāras may be felt in the chakra locations set out in books on Tibetan Buddhism. A book that I found very useful on this subject, and may be useful to others who find themselves on a 'self-discovery' path, was Foundations of Tibetan Mysticism (1957), by the German Buddhist scholar, Lama Anagarika Govinda. There are further clues in the Bardo Thodol. One of the main things that we learn from long-term meditation practice, from the practice of Focusing, and from the practice of Mindfulness, is that the nature of the body-mind and of the process by which the brahmavihāras are embodied in us, is mysterious and cannot be easily explained. It is further complicated by the fact that men and women tend to embody the kleshas and brahmavihāras in ways that are in some ways opposite to each other. This is a complex subject, and I shall need to return to it in a future article in this series.

In the light of what I spoke about in the previous paragraph, I feel a need to emphasise that our practice on this 'self-discovery' path within Buddhism, or through Focusing, or through both together, has particular, very practical, aims and objectives. I hope to show in the course of this and subsequent articles, that because Focusing in particular, and 'self-discovery' practice in general, leads us to give importance to cultivating the brahmavihāras, it is also a profoundly ethical practice. It is a practice that, because it starts by building our familiarity with the brahmavihāra qualities of the 'clear space' and Presence, serves inherently to cultivate an ethical sensibility. Not only is the practice wise and compassionate, but also, inherently, it is deeply ethical – and like all true meditation practices, it facilitates the release of the obscuring kleshas that give the egoic mind its energetic and emotional momentum, and apparent substance.

It is of great importance, in my view, that we keep in mind this association between 'self-discovery' and ethics. I have come across rather odd understandings of Vajrayāna, where students (and teachers) get it into their heads that Vajrayāna is a perspective on practice where ordinary ethical considerations do not apply, or that ordinary human physical and psychological limitations do not apply. This is a very unfortunate and inaccurate view. For me, the 'self-enquiry', or 'self-discovery', path that I have been simply calling, for brevity, Vajrayāna, is just the logical next step after we have entered into an Other Power ('self-surrender') approach to practice.

In the Other Power frame of reference for practice we recognise the power of the dharmic reality – a psycho-spiritual reality that is felt to be beyond us and outside of us. We recognise its power to support us in our spiritual transformation, and therefore surrender to that reality in our meditation practice. In the Vajrayāna, or 'self-discovery', stage we take this attitude of meditative receptivity a step further – we entertain the possibility that the dharmic reality is not separate from us; that all existence is permeated by the dharmic reality; that the dharmic reality within us but obscured by the kleshas, and by our tendency to fall into egoic identification. So in the 'self-discovery' perspective we take the dharmakāya and sambhogakāya seriously – as descriptions of the dharmic reality, and of who we ultimately are.

This alignment with the dharmic reality that we undertake in the ‘self-surrender’ (Other Power) and ‘self-discovery’ (Vajrayāna) stages, brings us into a profound deepening of our ethical sensibility. This is especially so if you are practicing the brahmavihāras, since it is by establishing these four aspects of Positive Emotion that the egoic kleshas are, over time, comprehensively removed from the body-mind. Our recognition, through Other Power practice of the brahmavihāras, that the mahabrahmavihāras are always available as a source of emotional healing, brings a profound shift in our approach to both ethics and meditation practice. When we make the further realisation, through our embrace of the Vajrayāna perspective, that the benevolence of the brahmavihāras is always in some sense ‘within’ us (even if they are often profoundly obscured), takes us to an even deeper level in our spiritual process. Indeed it brings us to a place where we begin to recognise that ethical conduct and compassionate responsiveness are our natural state – if only we can continue to move beyond the reactivity of the egoic mind, by releasing the kleshas through brahmavihāras practice.

Gendlin’s Focusing gives us an opportunity to examine the reactivity of the egoic mind in minute detail, and an opportunity to ‘step back’ out of identification with that reactivity, into the Mindful Presence or ‘clear space’ that is ever-present at a deeper level. By repeating this movement of dis-identification, we become familiar with the attitudes of Consciousness that are the internal characteristics of Mindful Presence – and we come to recognise that the most fundamental of these attitudes of Consciousness are the brahmavihāras.

© William Roy Parker 2025

Consider reading the next article in the Buddha Meets Gendlin series:

5. The Six Realms as Archetypal Psychology

One of my overall goals in this series of articles, has been to try to establish the correct correspondences in my Buddhist reader's minds, between the cognitive-perceptual components that the Buddhist tradition calls the ‘five skandhas' and the four primordial positive emotions that the Indian tradition calls the b…