5. The Six Realms as Archetypal Psychology

Discerning the place of the brahmavihāras in Padmasambhava's 'hermetic' system of spiritual psychology.

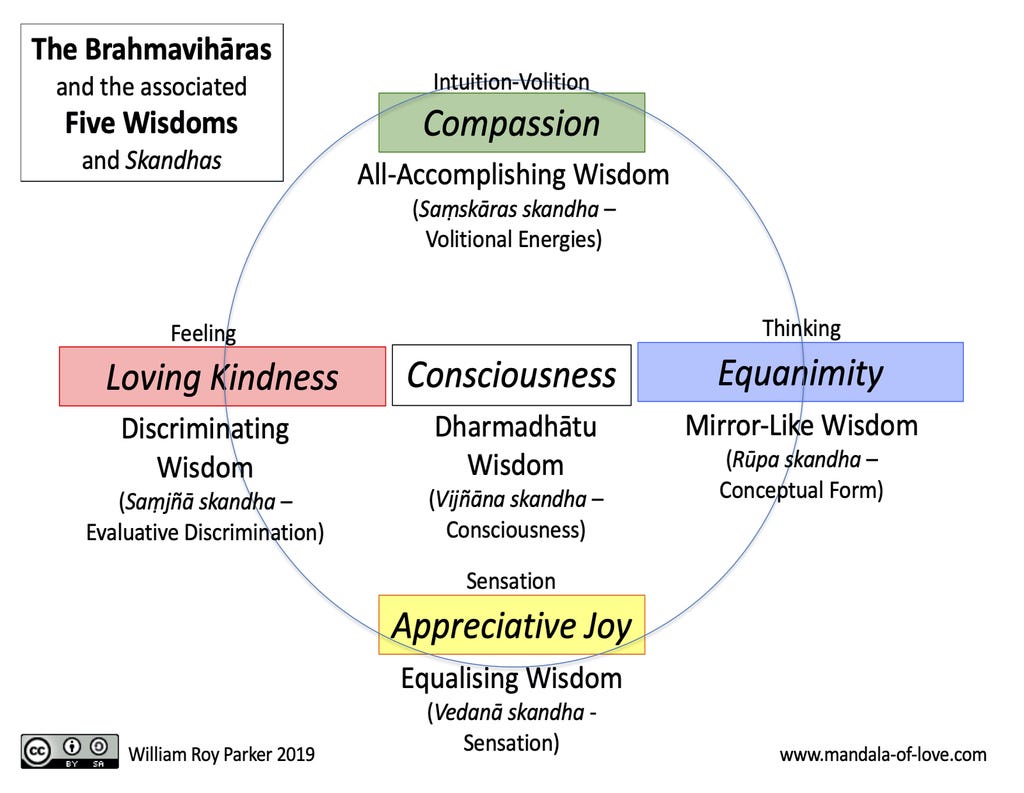

One of my overall goals in this series of articles, has been to try to establish the correct correspondences in my Buddhist reader's minds, between the cognitive-perceptual components that the Buddhist tradition calls the ‘five skandhas', on one side; and the four primordial positive emotions that the Indian tradition calls the brahmavihāras, on the other. These two sets of principles are foundational for meditation and Mindfulness practice, and for the Buddhist approach to wisdom – or insight into the 'empty' nature of the self. These two sets of principles are difficult to grasp when approached in isolation. By studying them together, and studying their relationship however, both sets of Dharmic principles are revealed.

In order to establish the correct correspondences – correspondences that I have been characterising as archetypal, or 'hermetic' – I need to first explain the other sets of correspondences that have been put forward. I have taken time in this article to provide the rationale for all of the sets of correspondences that I am familiar with, so that readers can make their own assessment of what works best – what 'feels' right experientially, and what is most practically supportive in the context of meditation and contemplative practice.

While this process of finding the correct correspondences between the skandhas and the brahmavihāras may seem unrelated to my exploration of the commonalities between Buddhism and Focusing, I hope to illustrate in the course of this process, the fact that this pursuit of conceptual congruence – this pursuit of Dharmic conceptualisations that really fit our experience, and can therefore truly serve us – is an expression of one of the core skills of Gendlin’s Focusing method, and is one of the major benefits that Focusing can bring to Buddhist practice.

This article is the fifth article in my ‘Buddha meets Gendlin’ series. The first article in the series was Eugene Gendlin's 'Clear Space' and the previous article in the series was The Inner Path of Ethics.

The Five Skandhas and Five Wisdoms

Returning now to the 'mandala wisdom' of Tibetan Buddhism, those who are familiar with the way Buddhist philosophy and practice developed as it evolved into its Mahayāna and Vajrayāna phases, will recognise Buddhism's five-fold model of the mind and of the dharmic reality – the teaching of the Five Wisdoms that emerged and flourished in those centuries. Indeed, the Dharmadhātu Mandala, the mandala of the ten Buddhas that we find in the Bardo Thodol texts, is often simply called the Five Wisdoms mandala. Clearly, the skandhas and the Wisdoms are inseparable expressions, at different levels of reality, of the same archetypal principle, since recognition of the 'emptiness' of each of the five skandhas brings with it the revelation of the corresponding dimension of Wisdom.

Unfortunately however, students of Buddhism tend to study the three yānas (Hinayāna, Mahayāna, and Vajrayāna) in isolation, so they usually miss the fundamental connections between the skandhas, the brahmavihāras (which we find in the Theravada Pali Canon) and the Wisdoms (which we find in the Mahayāna and Vajrayāna). They also miss another key set of correspondences – that between the five skandhas and the five categories of obscuring kleshas that I have mentioned above. To the extent that we identify with the skandhas and fail to recognise them as 'empty', the egoic mind accumulates the corresponding kleshas. Indeed, without the dis-identification that comes from deep Mindfulness practice (such as may also be cultivated through Focusing), the kleshas accumulate an energetic momentum that is hard to reverse – even when there is heroic and self-sacrificing moral idealism and an earnest commitment to ethics practice and compassionate activity in the spirit of the bodhisattva ideal.

It is perhaps understandable that the Buddhist tradition should fail to acknowledge the associations between the four brahmavihāras and the various sets of five Dharmic principles that we are presented with in the Bardo Thodol – the link between the set of four brahmavihāras, and the sets of five, is not at first apparent. There is always however, an implied fifth element in the brahmavihāras model, which is Consciousness – the 'empty' vijñāna skandha. The brahmavihāras are, after all, not just profound ethical and relational principles that we can undertake to cultivate in a spirit of moral idealism. Ultimately we need to understand them as the inherently ethical and relational 'attitudes' of Consciousness that are inherently present in the collective depths of the mind.

Drawing on the language of Neoplatonism, the brahmavihāras that we experience in meditation and in our personal lives, as aspects of Positive Emotion, are emanations on the surface, or nirmānakāya level, of the mind, of archetypal principles that a present at the dharmic level (the sambhogakāya and dharmakāya levels) – beyond the egoic mind, but nevertheless essential to who we are as human beings. These depths are revealed through deep Mindfulness practice, which in my view, inherently involves recognising that Consciousness is an expression of the dharmic level of the mind. By repeatedly 'resting as' the 'clear space' of Consciousness, we release the kleshas that are obscuring Presence, and deepen our experience of Mindfulness. I shall be returning to this theme later.

The Kleshas and the Brahmavihāras

In the course of these articles, I shall be talking about the skandhas, kleshas, Realms, brahmavihāras, Wisdoms, and male and female archetypal Buddhas. I shall be addressing them as sets – something that is, unfortunately, fairly unusual. We need to address them together in this way because each group needs to be understood as a constellation of Dharmic principles that share an archetypal root or theme. It is only by contemplating them together that we can recognise the logic of the correspondences between them. When we see the archetypal theme that runs through each of the five groups – finding a very different expression in each one – all of them are revealed in a new way, and the ten archetypal Buddhas of the Dharmadhātu Mandala also come to life for us. As a Buddhist student of Gendlin's Focusing, I find the brahmavihāras and the kleshas to be crucial pieces of the spiritual development puzzle because they are both bodily-felt – because they both address the somatic, or body-mind nature of the process.

The correspondences between these sets of Dharmic principles are complex, because they allow us to understand how the same cognitive-perceptual function – the same skandha – can manifest either in a negative and dysfunctional way in the egoic mind, or in a positive and even sublime way (i.e. as one of the five Wisdoms), once our egoic identification with them is released. As a way of talking about the fact of the archetypal connection between the 'lower' and 'higher' expressions, we can, using a term from Neoplatonism, say that the members of each set of Dharmic principles, while they appear very different (or even as opposites) are in fact 'hermetically' related. Below in this article, I shall endeavour to provide an introductory outline to these five sets of hermetically connected principles, taking the opportunity as we go, to highlight the ways in which Gendlin's Focusing practice can serve to bring us to a discovery of the same five facets of Wisdom that we find presented in Vajrayāna Buddhism.

I reference this notion of hermetic relationship, because it is very important to understand that our state of unconscious egoic identification with the skandhas and kleshas, on one side; and the corresponding states of sublime meditative receptivity that we call the brahmavihāras, on the other, are not opposites as we conventionally understand that idea. Indeed it is this understandable, but rather narrow conceptualisation that sees the skandhas (and kleshas) as opposites, or antidotes, to their corresponding brahmavihāras, that has lead to various different sets of correspondences being put forward.

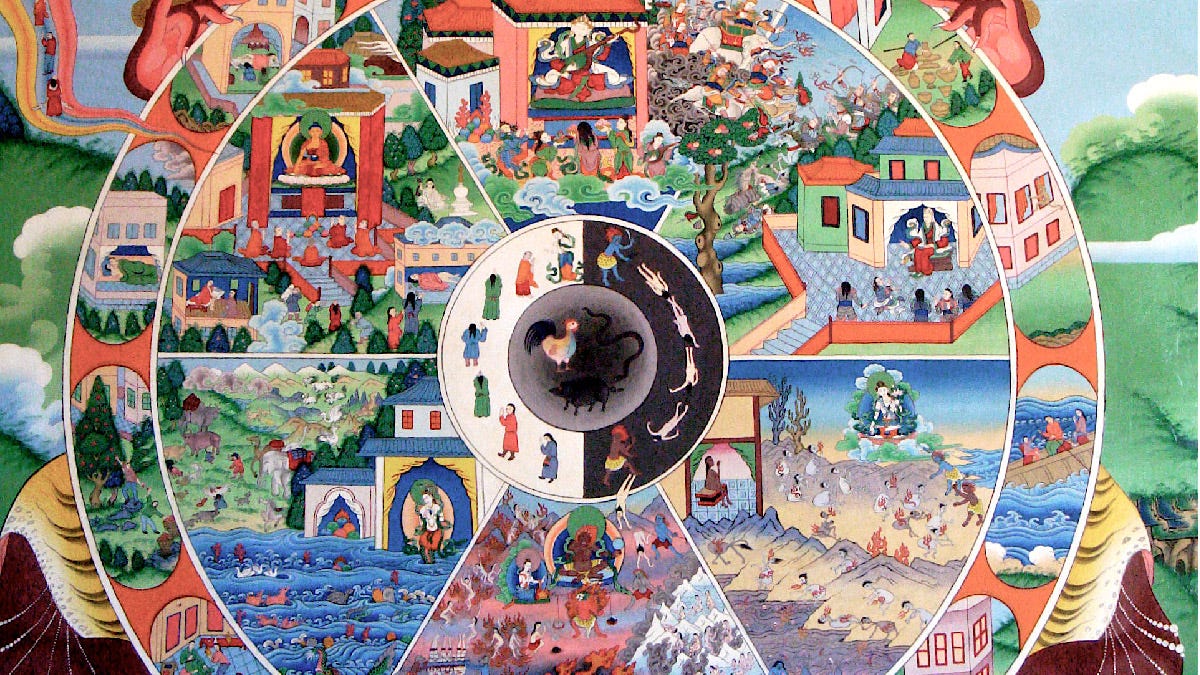

A common confusion has arisen in regard to the way the brahmavihāras are placed within the set of mandala correspondences – indeed there appear to be at least three completely different sets of correspondences, and several completely different ways of approaching the whole issue. A common approach in the earliest periods of Buddhist history was to identify the brahmavihāras that best function as antidotes – opposites that serve to 'overcome' the predominant kleshas in each of the traditional Realms of the Buddhist 'Six Realms' cosmology. The bhāvachakra, or 'Wheel of Life', images that have come down to us from those early centuries depict a mythic Buddha figure in each of the Realms, each Buddha holding a symbolic object to indicate the antidote to the klesha that is the characteristic egoic trait of that particular Realm.

A Review of the Psychology of the Six Realms

The fact that the antidotes, or opposites, symbolised in the 'Wheel of Life' imagery are often brahmavihāras has led to an approach to the brahmavihāra correspondences that is guided by this idea of identifying brahmavihāras that might function as antidotes, or opposites, to their associated skandhas and kleshas. My own approach is different, and follows the 'hermetic' or archetypal approach that we find in Vajrayāna Buddhism. I shall explain my approach further below, but essentially it is one in which the brahmavihāras are presented, not as opposites, but as the components of Positive Emotion that correspond to the Wisdoms. There are only four of these associations – those that are associated with the four cardinal points, or quadrants, of the mandala. The vijnāna skandha (Consciousness) in the centre of the mandala, has no associated brahmavihāra – rather it is intimately related to all of the brahmavihāras. We may even say that the brahmavihāras are the attitudes of Consciousness (vijñāna) – the attitudes of truly Mindful Presence.

Because so much of the vast literature of early Buddhist history was erased by the burning of the Buddhist libraries by the Muslim invaders, it is not clear at what point various mythic Buddha figures with particular qualities began to associated with the Six Realms, but this is believed to have been an early development. The idea that there are five Wisdoms, being five Enlightened modes of cognition and perception, that arise when the five skandhas are 'seen through' and recognised as 'empty', was a later, and entirely separate, and much more important development in the Mahayāna period – leading naturally to a mandala of, first five archetypal Buddhas, and then five 'Buddha couples', as embodiments of those five Wisdoms.

By the time of later texts like the Bardo Thodol of Tibetan Buddhism, the correspondences between the skandhas, kleshas and Realms had become well established – as had the idea that the five Wisdoms are inherent in the mind, and are naturally revealed as the practitioner releases his identification with the five skandhas, and recognises them as 'empty'. The associated idea of approaching the brahmavihāras as aspects of the Wisdoms, and as the mahabrahmavihāras (i.e. aspects of the dharmic reality, inherent in the depths of the mind), takes us to a somewhat different, and I would say deeper, place – as I shall explain below.

The approach that I have been taking to the associations between the skandhas and kleshas, on one side, and the corresponding brahmavihāras and Wisdoms, on the other, is one found in the Vajrayāna Buddhism of Tibet. This approach, or perspective, has usefully been distinguished from the earlier stages of the Buddhist tradition's developmental process, by identifying it as a 'self-discovery' perspective. This approach does not deny the value of the previous 'self-development' (Hinayāna) and 'self-surrender' (Mahayāna) stages – indeed 'self-discovery' (Vajrayāna) should be regarded as a three-fold view that is nested within those two previous perspectives. I shall be making use of this three-fold framing of Buddhist philosophy a number of times in this series of articles. It is a way of resolving the apparent differences, and even incongruities, that we see in Buddhist philosophy, and is known by many Buddhists as the 'Three Myths' model – after a 2004 paper by Dharmachari Subhuti, in which this terminology was introduced.

I am, in this article, giving emphasis to this 'self-discovery' approach, since there are so many elements in Gendlin's Focusing model that appear to affirm it and correspond to it. Before moving on to a more detailed framing of my 'self-discovery' approach to the connection between the brahmavihāras and skandhas in my next article – an approach in which the brahmavihāras and skandhas (and Wisdoms) are acknowledged as being archetypally, or 'hermetically', linked; I would like to briefly outline how the 'self-development' approach works in this context. I need to explain why the logic of a 'self-development' approach to practice brings us to a different set of correspondences from the 'self-discovery' approach.

If Buddhist students are thinking within the 'self-development' perspective, then they naturally think in terms of identifying antidotes and opposites to the skandhas and kleshas, rather than in terms of turning inwards towards an inherently present, positive hermetic correspondence, on the sambhogakāya level of mind, of the egoic dysfunction that is present on the nirmānakāya level.

Equanimity (upekshā) and the Hell Realms

So, asking ourselves, within the 'self-development' perspective, what the 'opposite', or 'antidote' of the Hell Realm klesha of dvesha ('hatred'), might be, we may, quite naturally and understandably, choose mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness). Love is, after all, conventionally understood to be the opposite of, or antidote to, hatred. Another strand within the Buddhist tradition, following a different logic, identifies the key antidote to the Hell Realms as karunā, or Compassion – since our response to those who suffer is not just love (mettā/maitri), but Compassion (karunā). The bodhisattva figures depicted in the Hell Realms in the traditional bhavachakra, or 'Wheel of Life', imagery, a shown bringing fire (which symbolised mettā/maitri), or a water vessel (which carries the soothing balm of karunā).

Those in whom identification with the rūpa skandha leads to enemy-images and dehumanising narratives, and therefore generates dvesha, or hatred, might indeed do well to cultivate mettā/maitri or karunā. Within the 'self-discovery' perspective however, the positive, or sambhogakāya reflection of that judgmental mode of cognition that Buddhist tradition calls the rūpa skandha, is the Mirror-like Wisdom, which is that way of being which recognises, and rests 'as', the primordial purity and stillness of the ultimate reality. The corresponding brahmavihāra to the Mirror-Like Wisdom, and the meditative path by which the Mirror-Like Wisdom is realised, is upekshā (Equanimity) – as I shall be explaining further below. This illustrates the ‘hermetic’ character of Padmasambhava’s psychology. Upekshā, in this instance, is not being applied as an ‘antidote’ or a ‘response’ to the klesha category of dvesha (hatred) - rather it is the related archetypal principle. When we recognise and rest ‘as’ the primordial stillness of upekshā, our Hell Realm karma self-releases.

In the mandala, the male Buddha figure who traditionally represents the Mirror-Like Wisdom is the imperturbable and pure white figure of Vajrasattva-Akshobya – a figure who more powerfully embodies the receptive, 'internal', or 'self-regarding' aspect of the brahmavihāra of Equanimity (upekshā) than any other figure in the mandala. In its earliest form the eastern quadrant of the mandala was dark blue – the colour of the Buddha Akshobya. In more recent centuries, the colour of the eastern quadrant is more often white – the colour of Vajrasattva – because of the great importance given to this bodhisattva form of Akshobya, who is white in colour.

It is important to see the Mirror-Like Wisdom as a faculty of true mental objectivity. It is the attitude of Equanimity that brings a release of egoic mental patterning within the describing, conceptualising, and form-creating function of mind that the Buddhist tradition calls the rūpa skandha. While the practice of Loving Kindness certainly cleanses the emotional or evaluative aspect of perception, since it leads to a release of egoic patterning within the evaluative samjñā skandha function of mind (and therefore also leads to the Discriminating Wisdom), clearly the key factor contributing to mental objectivity, is the brahmavihāra of Equanimity.

[For more on this important understanding of upekshā as the aspect of Positive Emotion that brings mental stillness and non-reactivity, and serves to release the klesha of dvesha, or ‘hatred’, you my wish to read a later article in this series: The Brahmavihāra of Equanimity.]

Compassion (karunā) and Asura Realm

A second example of the application of the 'self-development' approach, and of our natural tendency to think in terms of opposites and antidotes, rather than in terms of 'hermetic' or archetypal relationships, is seen in the way the brahmavihāra of muditā (Appreciative Joy) is often seen as the brahmavihāra that 'overcomes' the klesha of irshya (envy), which is generated by the volitional samskāras skandha, and finds expression in the envious rivalry, warfare, and manipulation of the archetypal Asura Realms. Elsewhere within the early Buddhist tradition the suggested key antidote to the Asura Realms is patience – a quality symbolised by a sword, or a vajra.

I am not wanting to fundamentally negate the 'self-development' strategies. I use them myself, and find them perfectly valid within a more external and relational context. When I have to work with people whose temperament expresses the traits of the asura archetype, I instinctively know to diffuse the conflictual tendency in the interaction by finding qualities of appreciation and patience in myself. The concern that is motivating me to offer different brahmavihāra correspondences, is regarding the inner dimension – the correct correspondences in the context of innerwork and meditation.

Appreciative Joy (muditā) does appear to offer a logical opposite, or antidote, within the interpersonal domain, and within the 'self-development' approach, to the klesha of irshya (the klesha category of ‘envy’ that characterises the Asura Realm). Padmasambhava’s psychology however, once again follows an inner ‘hermetic’ logic – the logic of archetypal psychology, and of the Vajrayāna path of 'self-discovery'. This approach tells us that the karma of the Asura Realm, because it arises from the way the egoic distortion of the volitional and intuitive samskāras skandha, gives rise to the envious, wilful, and manipulative klesha of irshya. What ultimately heals this is the volitional aspect of dharmic reality, which the tradition speaks of in terms of karunā (Compassion), and the All-Accomplishing Wisdom. The intuitive, empathetic, and needs-awareness, which is integral to Compassion (karunā), clearly work much better than Appreciative Joy (muditā) as way of helping us to familiarise ourselves with the All-Accomplishing Wisdom, and with the particular aspects of Enlightenment that are personified by the green Buddhas of the northern quadrant – Amoghasiddhi and Green Tara.

The samskaras skandha denotes the volitional component of mind – and also points to the mind's conscious or unconscious intuitive recognition of intangible volitional processes and dynamics. The corresponding Wisdom, within the hermetic or archetypal approach to psychology that characterises the Vajrayāna has to be the All-Accomplishing Wisdom – since this is a mode of intuitive perception and of skilful psychological responsiveness that quite specifically goes beyond the cultivation of opposites and antidotes, and instead seeks a path of reconciliation in which opposition and conflict is avoided. The meditative path by which we cultivate the All-Accomplishing Wisdom is karunā (Compassion), which is the ‘volitional’ component within the brahmavihāras model of Positive Emotion. While that in us that is psychologically asura-like does indeed need to learn the value of Appreciative Joy (muditā), the character of the aspect of positive emotion that naturally unfolds when that tendency is seen through, is Compassion (karunā).

So what I am pointing out here, is that just as the four skandhas of the quadrants of the mandala can usefully be regarded as the sensory (vedanā), evaluative (samjñā), intuitive-volitional (samskāras), and describing-objectifying (rūpa) components of the mind; so too can the four corresponding brahmavihāras be regarded as the sensory (muditā – Appreciative Joy), evaluative (mettā/maitri – Loving Kindness), intuitive-volitional (karunā – Compassion), and describing-objectifying (upekshā – Equanimity) aspects of Positive Emotion.

Both the 'form-creating' skandha of rūpa that objectifies through description and conceptualisation, and the associated brahmavihāra of Equanimity (upekshā) are easily misunderstood and neglected, but both play a key role. The two are hermetically, or archetypally related. As the mind's mechanism of objectification, concretisation, and reification, the rūpa skandha is foundational to the egoic mind's habitual denial of reality. In a similar but opposite way, the primordial stillness of the mahabrahmavihāra of upekshā (Equanimity) is an archetypal healing principle that provides a basis for our development of interpersonal non-reactivity within the four brahmavihāra components of Positive Emotion. By bringing awareness to, and breaking our identification with, the mind's mental descriptions and reifications, Equanimity can be characterised as opening the door to the world of Positive Emotion that is the brahmavihāras.

The female Buddha figure who represents the All-Accomplishing Wisdom is Green Tara – an extremely important and very popular figure in the Tibetan pantheon. She is believed to embody an intuition and Empathy so infinitely powerful and expansive that it allows her to release beings from their unconsciousness across the universe – just by the power of her meditation. While she extends herself intuitively and imaginatively through the mental activity of Empathy, she is also depicted as concretely and externally active – as 'stepping down' into the strife of samsāra out of Compassion. While her Wisdom is that intuitive intelligence that is called the All-Accomplishing Wisdom – the Wisdom that can challenge and unravel the envious desire and power-drive of the asura mentality.

So Green Tara's primary quality is Compassion. It is probably fair to say that all Buddhas embody Compassion in some way. Green Tara however, is regarded as a representation of the very essence of the active and 'other-regarding' aspect of karunā (Compassion). To understand her connection with the asuras, we need to think of Empathy as a form of intuition that overcomes the self-other dichotomy and therefore leads directly to a the volitional response of Compassion. Intuition is also a characteristic of the asuras, but theirs is a self-serving intuition – an intuition that is without empathy or Compassion. Intuition tends to lead to fear, and in the asuras this fear leads to control. Worse still, it leads to violence and intimidation and all manner of self-serving manipulations and cruelty, as fear is denied within while being cultivated in others.

[For more on this important understanding of karunā as the volitional aspect of Positive Emotion that serves to release the klesha of irshya, or ‘envy’, you my wish to read a later article in this series: The Brahmavihāra of Compassion.]

Loving Kindness (mettā/maitri) and the Preta Realm

A third example of the application of an opposition, or antidote, approach (i.e. 'self-development') to the correspondences between the skandhas, kleshas and Realms and the brahmavihāras, is the association that is made between the great red Buddha Amitabha and karunā (Compassion). While Amitabha and Pandaravarsini, the male and female Buddhas of the red, western quadrant of the mandala, are clearly abundantly compassionate, karunā does not, in my view, show us their quintessential characteristics as well as does mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness). The Realm associated with the emotional and evaluative samjñā skandha is the Preta Realm – a domain characterised by the klesha category of rāga, or ‘craving’, that generated by the samjñā skandha. This is another instance of a choice of correspondence that is based on our assessment of what brahmavihāra quality that the pretas might need, rather than the distinctive brahmavihāra quality that is archetypally or hermetically associated with the Discriminating Wisdom and embodied in the figures of Amitabha and Pandaravarsini.

To understand why the Vajrayāna tradition would associate mettā/maitri with the Discriminating Wisdom, we need to understand how the evaluative function of mind that we call the samjñā skandha, is transformed when we release our identification with it. Through the detailed and sustained practice of Mindfulness, such as we may gain through the practice of Gendlin's Focusing, we step out of that egoic identification into an entirely different way of being, that is nevertheless archetypally related to samjñā. In place of the rāga (craving) that is generated by our identification with the samjñā skandha – a state in which all satisfaction is felt to be outside of us, we find ourselves resting 'in' and 'as' the uncaused happiness that arises from the unconditional love that Buddhist tradition calls mettā/maitri. Our perception of the world from this place of mettā/maitri (Loving Kindness) is completely transformed. Mettā/maitri brings not just a sense of emotional nourishment and emotional completeness, but of a capacity for discernment through feeling – a new sense of fine judgement in the emotional and relational realm. It is this exquisite discernment based on the unconditional love of mettā/maitri that Buddhist tradition came to call the Discriminating Wisdom.

It is deeply instructive to recognise how the lens of the more conventional 'self-development' view takes us to different Dharmic understandings of these fundamental questions than does the 'self-discovery' approach. Another quality of Enlightenment that we find conventionally associated with the Preta Realm in the Buddhist 'Wheel of Life' is generosity. Once again, this has a certain logic to it within the interpersonal and 'self-development' frame. A person who habitually uses the evaluative samjñā skandha in a way that is self-referencing while also being undiscriminating and unconscious – always seeking a personal feel-good experience to comfort themselves – may indeed benefit from cultivating a more generous approach to life, in which they are truly interested in the wellbeing of others. Ultimately however the Discriminating Wisdom requires the deep emotional healing that comes from an Other Power relationship with mettā/maitri.

In the later historical development and Dharmic clarifications that we find set out in the Bardo Thodol texts attributed to Padmasambhava, we find Generosity associated with the figure of Ratnasambhava, and presented, along with Appreciative Joy (muditā), as one of the key healing principles for the Human Realm. The gift that Ratnasambhava instinctively gives is not just the gift of the Dharma – it is the gift of a Dharmic culture informed by muditā (Appreciative Joy). So it is the gift of the Dharma, richly, beautifully, and artfully expressed in a variety of concrete cultural forms. The culture of Buddhism, the culture of the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha), is inherently a culture of Appreciative Joy (muditā) – a celebration of the boundless spiritual potentiality that all human beings are blessed with, and a celebration of the great contributions and achievements of the Dharma practitioners of past and present.

So Generosity and Appreciative Joy both give concrete and sensory expression to mettā/maitri. In my experience however, the ultimate healing of that aspect of our karma that we might associate with the Preta Realm, comes through an Other Power relationship with the mettā/maitri that is inherent in the dharmic reality. The sense of faith and emotional stability that we gain when we gain real confidence in the benevolent and beneficial evaluative nature of the dharmic reality is quite remarkable. This quality of confident receptive relationship to mettā/maitri is personified in Tibetan Vajrayāna tradition by the beautiful blissful figure of the female Buddha Pandaravarsini. On a basic level we can take her as an embodiment of self-mettā, but at a deeper level she represents that aspect of the Discriminating Wisdom that is the Uncaused Happiness of those who rest in wide-open receptivity to the Loving Kindness of the dharmic reality, and know that they are loved. They know that they are loved, but loved in a way that is difficult to talk about – because they are loved in a way that is both non-personal and unconditional.

[For more on this important understanding of mettā/maitri as the evaluative, or valuing aspect of Positive Emotion that serves to release the klesha of rāga, or ‘craving’, you my wish to read a later article in this series: The Brahmavihāra of Loving Kindness.]

Appreciative Joy (muditā) and Human Realm

There is a fourth brahmavihāra association that we commonly find – one that once again gives expression to a different logic, though also not a hermetic one. This is the association of the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha (and the klesha of māna, and Human Realm, and of the yellow, southern-quadrant Buddhas, Ratnasambhava and Māmaki) with the brahmavihāra of Equanimity. This association arises, it would seem, because the particular reactivity that characterises the Human Realm is felt by some to need the quality of upekshā (Equanimity). This brahmavihāra does not appear to be our best fit for the Human Realm however. This association appears to have been made because the Wisdom associated with this yellow southern quadrant of the mandala is the Equalising Wisdom.

While the words Equanimity and Equalising have a verbal similarity in the English language, I do not believe that this, on its own, provides sufficient evidence of the deeper connection that we are looking for if we are seeking to practise in the spirit of the 'self-discovery' perspective of the Vajrayāna. Practising the brahmavihāra of Equanimity will not necessarily help us to open to the Equalising Wisdom in particular. The Equalising Wisdom is the recognition that all beings rest equally and evenly in the dharmic reality. While some of us are more conscious of this blessing than others, and we may construct a hierarchy of those who have realised their potentiality more fully, and those who have not, the implication of the Equalising Wisdom is that, whatever our differing degrees of realisation, capability, and value, on the outside, or in the world's terms; on the inside, the blessings of the dharmic reality are equally available to us, if we can only remove the obscuring kleshas.

There is a clear connection between the Equalising Wisdom and muditā (Appreciative Joy). While muditā is absolutely foundational to our relationships in the external world, it plays a different, and perhaps even more foundational role in our inner life – in our relationship with the dharmic reality. It was the group of insights that came to be called the Equalising Wisdom, that came together with other strands in Buddhist thought to give us the Tathāgatagarbha teaching – the Buddhist conceptualisation that gets translated into English as 'Buddha Nature'. Tathāgata was one of the epithets of the Buddha in the Pali Canon – a word that means 'thus-gone' (tathā, thus; gata, gone). The word garbha means womb, or embryo, or essence, so Tathāgatagarbha is a word with associations of vulnerability and fragility, and of maternal care and nurture, which came to refer to the innate potentiality for Enlightenment in all beings including the un-Enlightened. This notion of the tathāgatagarbha became a key conceptualisation in Vajrayāna Buddhism.

When, as we transition into an Other Power ('self-surrender') approach to practice, and our meditation takes on a more devotional-receptive character, the receptive aspect of muditā (Appreciative Joy) plays a very significant part in that new perspective. And when we transition again into the three-fold, or 'self-discovery', perspective of the Vajrayāna, we open even more fully to the somatic resonance within the body, of the muditā that exists on the sambhogakāya level of mind – experiencing ourselves as a channel for this aspect of the dharmic reality.

So the trikāya doctrine is another expression of the same sort of conceptualisation as we find in the tathāgatagarbha doctrine. By acknowledging the reality of the sambhogakāya, we are essentially entertaining the possibility that there are archetypal dimensions of Enlightenment in the depth of the mind that we can experience as visions and imagery, or as somatic resonances. Similarly, the dharmakāya connotes a level of the mind that is entirely non-personal and, in a manner of speaking already 'gone', free, and liberated. In reality, we cannot even say that this dharmakāya level of the mind is 'liberated' – it just never was not-liberated. In contemporary Tibetan Buddhism, the dharmakāya is usually personified by Vajrasattva. It is primordially pure, and while it blesses us, it is unaffected by anything we do. It is entirely 'empty', but can be experienced as Longchenpa's 'basic space of timeless awareness', and as Gendlin's 'clear space'.

Gendlin's Focusing teaches us to see the unfoldment that we call spiritual development in a very particular and very refined way that corresponds to the 'self-discovery' view. This three-fold framing of the Dharma challenges us to go beyond those forms of Dharmic conceptualisation that confine us to thinking in terms of finding opposites to our 'negative mental states'. Indeed it challenges even the notion of 'negative mental states' – inviting us to consider the possibility that what we might call 'negative mental states' are, in actuality, never separate from the all-pervading dharmic reality. A 'negative mental state' when framed within the 'self-discovery' view, can be be viewed with Equanimity (a key characteristic of Vajrasattva), and recognised as a mental state that is out of alignment with our Buddha Nature – out of alignment with our innate potentiality and deeper true nature on the level of the sambhogakāya and dharmakāya.

So the experience of 'negative mental states' is the experience of being tragically lost in the relatively superficial conditions of the egoic mind – alienated from the dharmic dimension of mind; and from the ever-present sources of Integration and Positive Emotion, which are the brahmavihāras and Wisdoms. In its model of how personality change happens, Focusing would frame our task as simply one of bringing the various energetic potentials that we carry within, into Consciousness, and resolving the conflicts between them. The 'negative mental states', in this view, are just constellations of skandhas. By nature 'empty', they dissolve when they are brought into the light of Consciousness.

I find myself needing to highlight the stark difference between the predominant 'self-development' model, on one side, and the more poorly understood 'self-discovery’ model, on the other. To distinguish these two conceptualisations and highlight the 'self-development' approach, we need to prevent the introduction of 'self-development' thinking into the domain of 'self-discovery'. Since the 'mandala wisdom' is really a 'hermetic' framework for understanding the nature of mind, the approach by which we identify the brahmavihāras that correspond to the skandhas, kleshas, Realms, Wisdoms and Buddhas in the Bardo Thodol, really must be an archetypal one. We need an approach that is in the spirit of the Vajrayāna, or 'self-discovery' perspective, and seeks to find a 'fit' between the principles that really ‘works’, not just intellectually, but experientially – as felt-experience within the field of the body. This 'spirit of the Vajrayāna' that I am speaking of here, is the approach that sees these 'mandala wisdom' relationships in terms of the common archetypal, or cognitive-perceptual theme within each quadrant of the mandala.

The brahmavihāra practice that best provides an experiential doorway into the Equalising Wisdom and into the spiritual character of Ratnasambhava and Māmaki, is muditā (Appreciative Joy). We need to remember that identification with the sensing and sensory vedanā skandha serves, within the dynamic structure of the egoic body-mind, to strongly confirm our sense of separateness from our fellow human beings – we feel physically separate even though we are, at the level of the dharmakāya, not separate at all. For me, it is this notion of 'separateness', that best expresses the klesha of māna, which characterises the Human Realm, and gets translated as 'pride'.

What characterises the Human Realm, when we see it from a spiritual perspective, is the preoccupation with personal identity, personal possessions, personal difference, personal skill and knowledge, and personal achievement. This is the 'pride' of māna – an affirmation of separateness and difference that finds expression in both our individual psychology and our group processes in society. In reality, this physical world of separation is pervaded equally and evenly by the dharmic reality, and the Equalising Wisdom is that archetypal healing principle within the sambhogakāya that transforms all this self-obsession into a sense of connection, solidarity, commonality, and a sense of shared humanity – a sense of wonder at human achievement, and at the beauty of this manifest world. Of the four brahmavihāras, the one that naturally corresponds to the Equalising Wisdom is muditā (Appreciative Joy), because it best expresses the sense of abundance and blessedness that naturally arises when we learn to rest out of identification with māna (pride), and set our experience of the sensory (vedanā) in a higher context.

[For more on this important understanding of muditā as the appreciative aspect of Positive Emotion that serves to release the klesha of māna, or ‘pride’, you my wish to read a later article in this series: The Brahmavihāra of Appreciative Joy.]

© William Roy Parker

Consider reading the next article in the Buddha Meets Gendlin series:

6. Padmasambhava's Hermetic Psychology

This is the sixth article in this series. You may wish to read from the beginning of the series: Eugene Gendlin’s ‘Clear Space’. You may also wish to read the previous article: The Six Realms as Archetypal Psychology – as that would serve to frame the information in this and the next few articles.